Is Arteta's Arsenal blueprint the solution to Barcelona's midfield conundrum?

Both teams have a penetrative left-back option that overlaps the inverted left-winger, a 1v1 specialist on the right with a right-back who cuts in to become a false pivot or interior.

Barcelona have traditionally been a very stubborn team. With their sense of pride, belonging and identity, it’s always been somewhat of a chore to instil change at the Camp Nou, even if it was obviously for the best. Take the reported case of now-former CEO of the club, Ferran Reverter. Even though the official explanation states he resigned for ‘personal reasons’, it’s often nigh-impossible to know the real truth.

Some reports even state Reverter didn’t like the Spotify deal and was advocating the club abandon the ‘soci’ model for its modern counterpart inspired by German football. Whether that’s true or not is anyone’s guess. But at the end of the day, it’s not unthinkable that Joan Laporta was unwilling to change something that’s been at the core of the club since its inception. Being one of the last examples of a football club led by the democratic rule of its members is something Barcelona are extremely proud of, even if it’s likely limiting them in the modern iteration of this sport.

Granted, this is a very extreme example, albeit one that perfectly demonstrates Barcelona’s inability - or unwillingness - to change. It’s true for the core elements like identity as much as it’s true for their sporting aspirations. There’s a reason every new coach has to have some sort of a Barcelona history; to put it bluntly, they are worried an outsider would divert too much from their mould, ultimately changing what was set in stone years ago. In my opinion, that’s one of the reasons why Barcelona’s next pivot will inevitably be a ‘Sergio Busquets profile’ and it’s also why we aren’t seeing structures that aren’t a traditional 4-3-3 survive for too long.

However, we’ve also concluded replacing Busquets will be a tiresome - and perhaps even impossible - task. On the other hand, the rise of a double-pivot structure among football’s elite is something we shouldn’t ignore. After all, the profiles the club has at its disposal seem to complement such a (minor) change in system.

So let’s see what it’s all about.

The double-pivot explained

While I was scouting for potential Busquets replacements, most of the elite names that have come up indeed play in some kind of a double-pivot structure. The traditional Busquets mould is very difficult to find, and even more difficult is to find a player who executes the role at such a high level as the LaMasia graduate. Modern midfielders are stronger, faster, far more aggressive and also quite capable with the ball at their feet.

But it’s this aggressiveness in their movement that makes them better suited to double-pivot structures next to a more stationary partner or even to floating no.8 roles just ahead of that same stationary teammate.

And given all of that, it’s easy to see why Busi is still the only viable single-pivot profile at the club. But the truth is that the end of his career is rapidly approaching. I’ve already explained in another analysis on the site why neither Frenkie nor Nico are the ideal single-pivot replacements for him but in tandem, they could potentially work. It is, however, conditioned by what you want your double-pivot to look like.

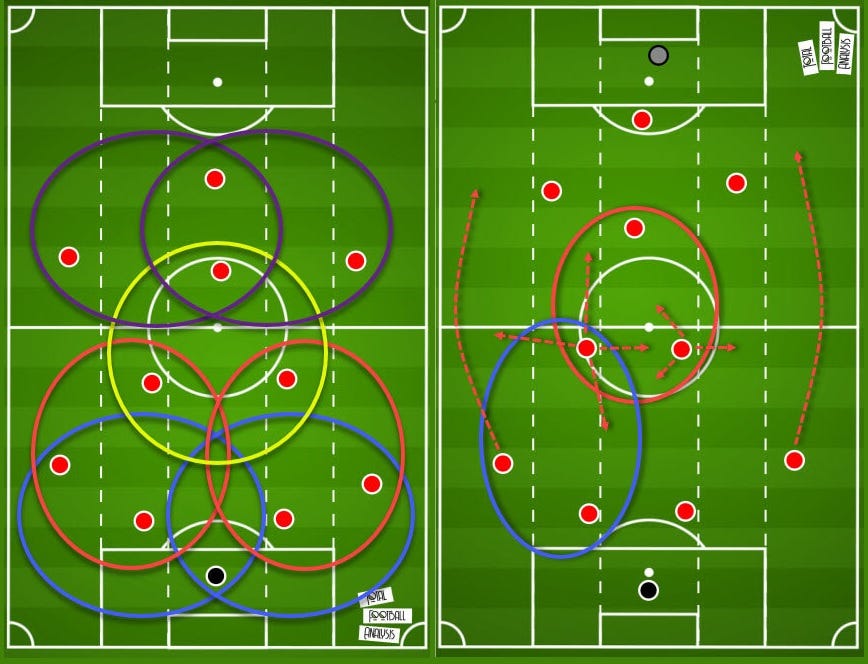

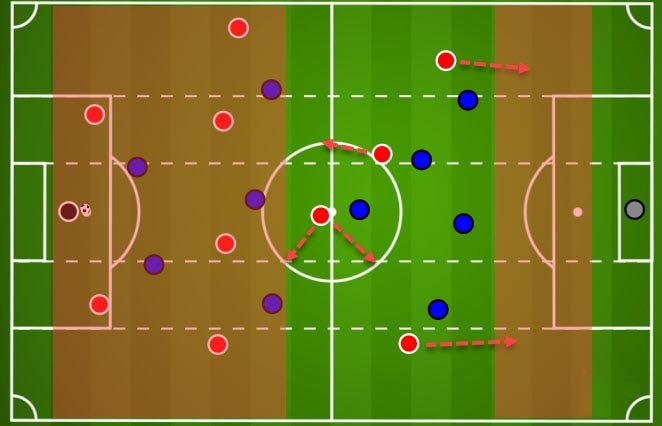

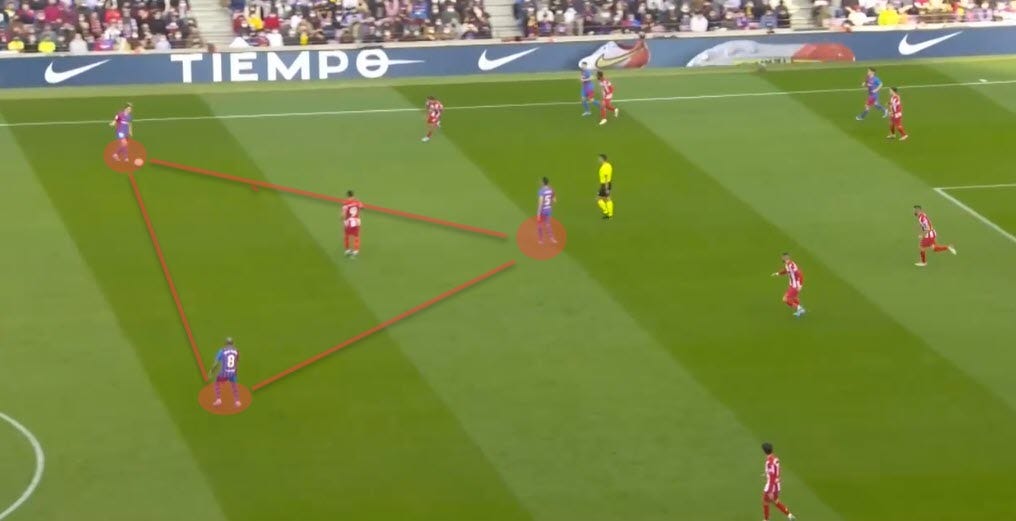

In a more general sense, a midfield duo usually consists of one more stationary profile and one more adventurous in his movement. Below is an example I’ve made for a piece that featured on TotalFootballAnalysis that specifically looked at attacking principles of a 4-2-3-1, a system that utilises the double-pivot.

The circles here represent the relationship between players and we can see the double-pivot’s responsibilities. One is far more stationary while the other gets a lot more freedom. But again, this is the ‘usual’ framework. It’s not uncommon to find two stationary pivots whose main task is providing stability, defensive control and progression from a deeper position. But as is the case with the other option too, it depends on the profile of midfielders you have at your disposal. Between Frenkie, Nico and Busquets, you could theoretically create the aggressive-stationary, stationary-stationary and aggressive-aggressive duo, with the last option most likely not being as viable.

That’s because you always want at least one of the pivots to maintain his position for the sake of compactness, stability and just plain defensive cover. Both of them leaving their position to attack the final third would result in acres of space for the opposition in the event of losing the ball. Seeing how both Frenkie and Nico love to run with the ball, often starting deeper but ending high, they’re not the ideal single-pivot options. But next to a more stationary partner, they could flourish.

Still, the 4-2-3-1 is far from the only system that can accommodate the double-pivot setup. Barcelona have already used that exact one under Ronald Koeman and Xavi himself has used his own variation of a double-pivot back at Al Sadd. I think the two likeliest options, however, are different variations of the 4-3-3 and the 3-4-3 structures, some of which we’ve seen in action fairly recently.

In the scenario in which either Frenkie or Nico are used alongside Busquets, it’s clear who would get what role. However, if we were to use Frenkie and Nico together, one would likely have to be more dosed and disciplined in his movement. At the moment, neither are exhibiting clear signs of being accustomed to a more stationary role but Nico has already played as a lone pivot for Barcelona B and is perhaps defensively more secure than his Dutch counterpart. Both, fortunately, are athletic, which aids them offensively and defensively.

It also helps that both can perform the aggressive role while the other can cover, making the attack more versatile and less predictive. In a more general setup, however, I’d argue giving De Jong more freedom would be the more sensible thing despite Nico’s growing attacking attributes. Ironically, however, for the time being, I still believe Busquets is the ideal partner for both players in a double-pivot, simply because he’s the elite stationary midfielder with vision, range and elite awareness. ‘But Dom,’ I hear you say. ‘Koeman has already used the double pivot and it did not work. How is this going to be any different?’ A valid question.

The Dutchman indeed did use the double-pivot of Frenkie and Busquets but to no avail. The problem is his system allowed for an aggressive-stationary dynamic but also didn’t really do anything to cover for Busquets’ lack of athleticism. Once Frenkie leaves his position and he remains alone, Barcelona lose compactness and Busi is once again stranded, or rather forced to cover a lot of ground by himself.

Koeman also didn’t use the other key cog in this scenario - the inverted right-back. But how does it even work and do we have a blueprint to follow? As the matter of fact, yes, we do.

Enter Mikel Arteta’s Arsenal.

Blueprint made in LaMasia

As Pep Guardiola’s understudy and former Barcelona player himself, Areta is very much the disciple of the same philosophy the Catalans have been following for years. He is a modern coach looking for inventions, positional play, superiorities and attacking football. His Arsenal side, even though still in development, mirrors those key elements of his ideology.

But the similarities between the Gunners and the Azulgranas are exactly what made me believe theirs is the very blueprint Barcelona could ‘steal’ to get the best out of their midfield. Arsenal are a team in heavy ascendancy and are projected to once again be among the very elite Premier League has to offer as early as the beginning of next season. While Barcelona have similar potential, it’s still far too early to tell if Xavi is heading in the same direction. But what we do know is that they have players of similar profiles who are, presently, used in a slightly different manner.

Both systems have a penetrative left-back option that overlaps the inverted left-winger, a 1v1 specialist on the right with a right-back who cuts in to become a false pivot or interior, centre-backs who start the build-up from the back and a striker who can drop to link-up play and create overloads through his movement and space occupation. But even more importantly, the Granit Xhaka - Thomas Partey double-pivot is exactly how Frenkie de Jong/Nico González - Sergio Busquets tandem could function to get the best out of the former two while slowly phasing out the latter.

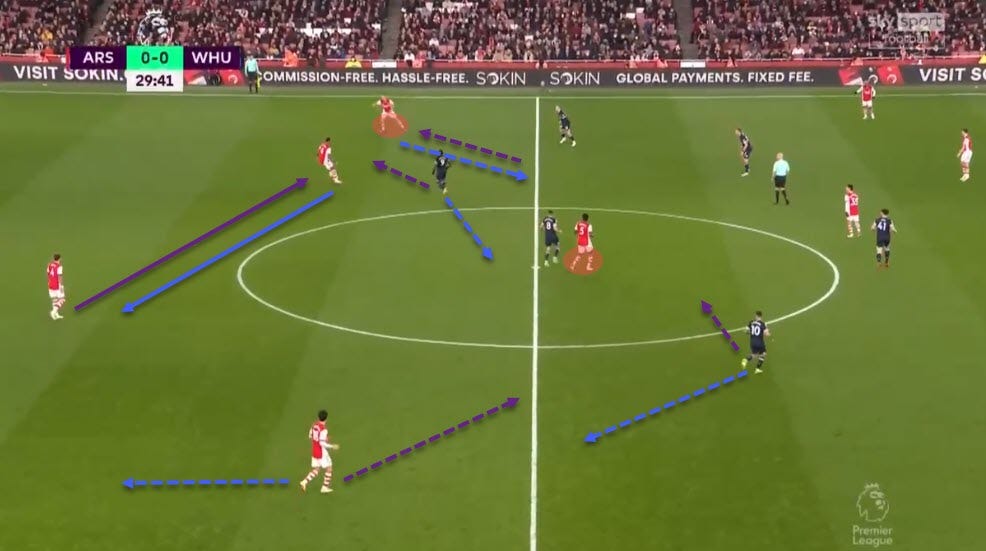

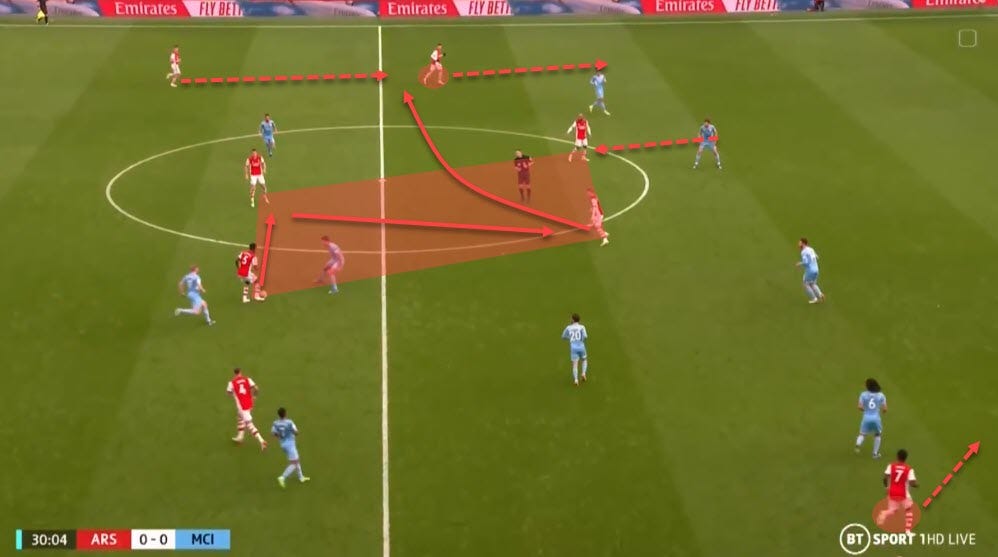

Let’s see their structure below.

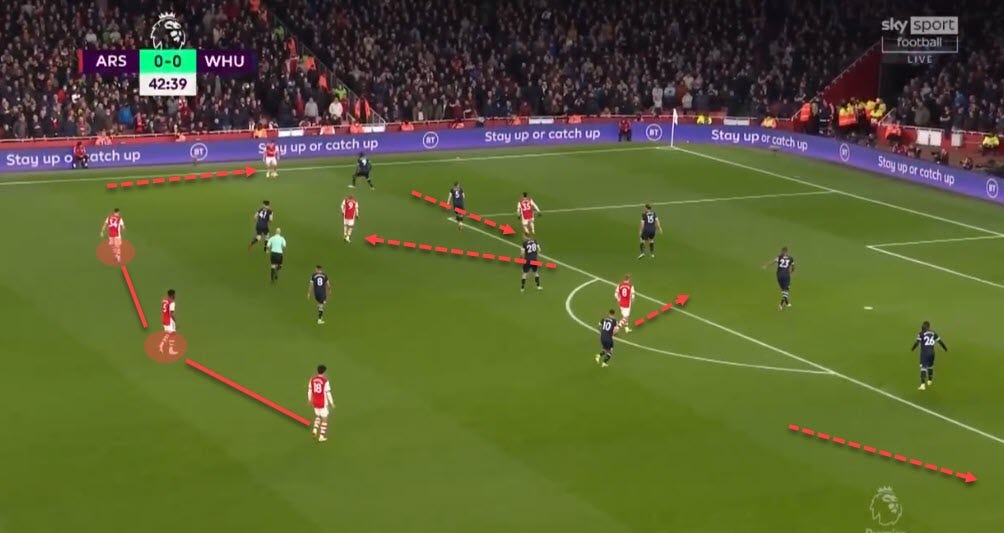

In this sequence, we’re paying attention to Xhaka, Partey and Takehiro Tomiyasu, Arsenal’s right-back. Notice the rotation in the middle of the pitch that occurs in the first phase of their build-up play. If the ball is recycled towards the left, Xhaka will drop into the LCB position to force West Ham United’s second line to react. If they don’t, Arsenal will have a 3v2 in the first line. At the same time, Tomiyasu will push up next to Partey to maintain the central overload and preserve the compactness.

If, however, the ball is recycled towards the right side, Xhaka pushes up next to Partey for that same overload and compactness while it’s Tomiyasu who drops deeper to create a 3v2 and force Manuel Lanzini to step out to press him. Arsenal do this to ensure superiority in the first phase and ultimately, force a 1v1 situation for Bukayo Saka on the right wing.

Here’s the full sequence in the GIF below.

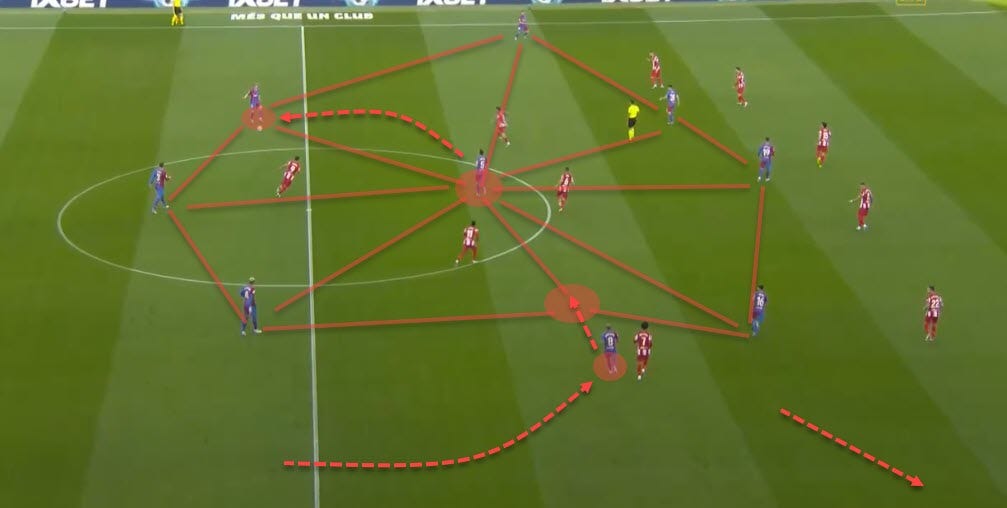

I found this very interesting because it mimics what Xavi had done in his latest victor over Diego Simeone’s Rojiblancos. Even though Barcelona didn’t officially use a double-pivot in that game, the structure still replicated the one you can see above. Instead of the Xhaka, Partey, Tomiyasu trio, we have Frenkie, Busquets and Dani Alves performing the same roles.

In possession, De Jong would drop from his midfield position to the LCB role, prompting Alves to push up into a false-pivot position next to Busquets. Again, this not only preserves the overload but also prevents Barcelona from losing their compactness in the middle. At the same time, since Busquets is the stationary pivot with the added cover of the inverted right-back, De Jong can start deep but still push up with the ball when needed.

Again, the goal is still very clear - get the ball to the isolated 1v1 specialist on the right side. For Arsenal, that was Saka while for Barcelona, it’s Adama Traore. This strategy worked quite well and Barcelona not only controlled but also dominated Atlético Madrid in the first half of the game. Among other reasons, it worked because it unlocked De Jong specifically.

In a traditional no.8 role, the Dutchman was often lost because he didn’t have the freedom to receive directly from the backline (or slot right into it) and then carry the ball forward via his elite progressive runs. The same would’ve happened had he been deployed as the single-pivot since Barcelona no.6s don’t get that sort of freedom of movement. However, the double-pivot can give him that while the inverted right-back then ensures it doesn’t negatively affect Busquets either.

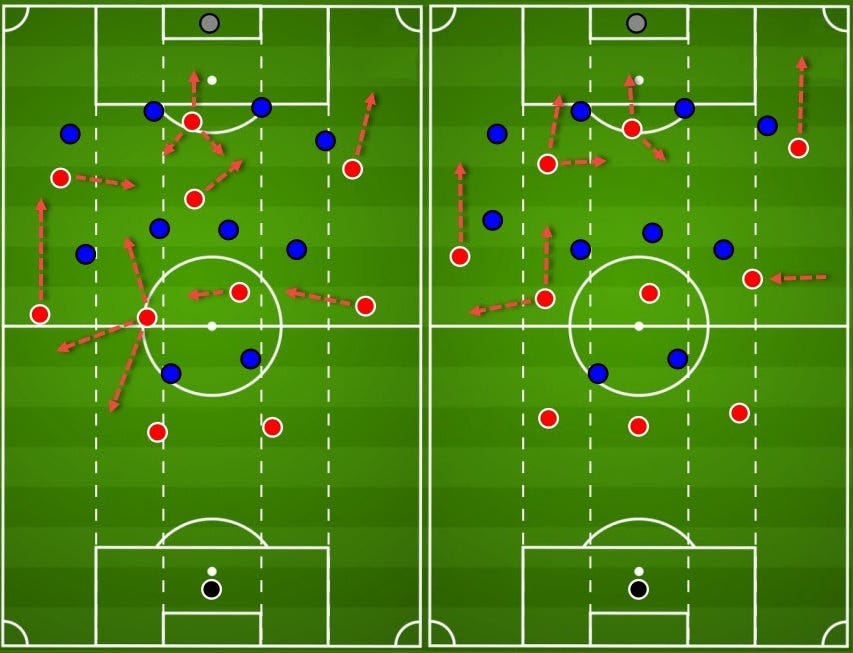

There are clear benefits of that in the face of a high press too. With a double-pivot, it’s much easier to overload the middle while also ensuring there are both short and long options available to escape the press.

This, again, is a blueprint from Arsenal that Barcelona can mimic with their player profiles. With an excellent ball-playing goalkeeper, the press can be escaped through short sequences. The double-pivot helps maintain numerical superiority in deeper areas while two penetrative profiles on the outside offer a long-ball outlet as well. Of course, if Xavi goes for a false-winger on the left in the form of Gavi, Jordi Alba becomes the outlet alongside Traore on the right.

The third midfielder and striker’s roles are similar; they’re active between the lines, disorganising the opposition’s structure and creating favourable situations for the outlets on the wings. In the instance above, the wingers have successfully been isolated against their markers.

These scenarios give the team flexibility of approach, meaning they can go short or long depending on the situation, the opponent or just profiles available at the time. But the double-pivot can be very helpful in transitional situations too. With two very press-resistant options occupying those central roles and one given the freedom to run forward with the ball, it allows for interesting sequences.

The way Arsenal cut through Manchester City by just using their double-pivot is essentially how I think Barcelona could operate should they go down a similar route. Both Frenkie and Nico have the ability to mirror Xhaka’s role while Busquets’ feints still send defenders the wrong way, the same way Partey dismarked himself in the video above. Carrying the ball is De Jong’s speciality and if given the licence to do so from a deeper midfield position, he will flourish.

This unlocks Barcelona’s tremendous transitional potential, especially with a Saka-type profile on the right (Traore) and players aggressively attacking the box in Ferran Torres and Ansu Fati. But it’s more than just that. We’ve already touched upon overloads against a high-pressing team and the same is true for stable phases of possession in the middle third of the pitch.

Arsenal, in particular, use the Xhaka/Partey duo to overload the midfield, combining it with a dropping striker in Alexandre Lacazette and someone like Martin Ødegaard as that third midfielder between the lines. This gives you a quartet in the middle with an option to then eject runners into space out wide.

Another example below.

This is also a good transitional weapon if possession is regained and recycled quickly. Barcelona have been speeding up their tempo of passing under Xavi and with a technically proficient midfield that can operate in tight spaces and under heavy pressure, central overloads can be a powerful weapon.

The same can be said for a more defensive outlook as well. Retaining the ball under pressure is far easier within a compact unit with players close to each other. The basic rule of thumb to follow is this: Does your teammate have a lot of time and space on the ball? If the answer is yes, then move away from him. If the answer is no, get closer. The double-pivot makes that easier to achieve.

But we’ve seen the defensive advantages of a similar setup already, both on and off the ball. Barcelona’s rest-defence has been abysmal for far too long, which has plagued their overall defensive performance. However, the double-pivot can solve that as well.

Let’s look at Arsenal first.

This is how the Gunners generally play in a settled possession phase in the final third. It’s eerily similar to what Barcelona can do. The left-back is high and wide, the left-winger cuts inside, the striker drifts for overloads, the third midfielder attacks the box and the right-winger holds the width and then attacks the box as well. However, it’s the rest-defence that we’re particularly interested in.

The double-pivot of Xhaka and Partey is joined by Tomiyasu, the right-back, and together they form a good safety net behind the attacking structure. Of course, Arsenal can and do use them for offensive purposes, as it should be. Tomiyasu can drift wide if necessary, Xhaka can push forward and Partey is the more adventurous passer with a good long shot if the deep block cannot be breached.

Barcelona have done a similar thing against Atlético Madrid. The double-pivot helped their pressing immensely while also providing a similar safety net in possession. Interestingly enough, it was Alves who joined De Jong behind Busquets but the premise remains the same.

By allowing Busquets to stay higher, you limit the space he has to cover when pressing. This is crucial because he’s very good at recognising when and who to press but lacks the legs to execute it if you ask him to cover acres of space. This is true for anyone. Even Partey struggles in the same regard for Arsenal if the Gunners lose their compactness. Athleticism will help here but no level of physical preparedness can cover up a lacking structure.

Another thing this system does is provide the safety net if Busquets is bypassed. I generally don’t like him in a heavy man-marking structure because he’s easily turned and bypassed in a direct 1v1 duel when he can’t outsmart his opponent or stay one step ahead of him. But generally, by ensuring midfield compactness, you limit the space in which he has to operate defensively. This is how you mask someone’s deficiencies by deploying him within a good system.

Finally, you reap the in-possession benefits of Busquets being positioned higher up by having De Jong and Alves behind him. But this won’t always be so. If Xavi is to use a natural double-pivot rather than inverting his right-back in the future, Busquets will be much deeper in possession. But staying with the defensive aspect, this compactness and covering less space is exactly how you improve Barcelona’s defensive transitions too.

In this sequence, we see Alves bombarding forward and as a result, Busquets and De Jong drop deeper as cover. With their compactness intact, Barcelona can easily collapse on the ball as soon as Atléti try to break following a lost ball. This is how you press efficiently; you do it by limiting the space you need to cover - it’s a collective effort more than anything else.

Final remarks

Barcelona and change are often two very distant terms. But given the profiles and the needs of the team at the moment, deploying a double-pivot could potentially be very beneficial, at least short-term. It’s not a coincidence this very structure is used by multiple elite European teams. Positional play is not limited to the 4-3-3 structure, even though that system lends itself to triangles quite nicely.

Variations of that same 4-3-3, 3-4-3 or 3-2-5 are all viable options for Xavi to experiment with while still staying true to Barcelona’s philosophy. Let’s see what the Maestro does next but the Arsenal blueprint is showing real potential.