What can we learn from Barcelona's preseason?

Preseason can be a cruel mistress. It seemingly gives you so much but in reality, it’s mostly just an illusion; a mirage of what you want to be true rather than what is true.

Preseason can be a cruel mistress. It seemingly gives you so much but in reality, it’s mostly just an illusion; a mirage of what you want to be true rather than what is true. So we’ve learned over the years not to trust it. Disregard it, even. But preseason has its value too. It is somewhat vague, sure, but it exists nonetheless.

Still, a general rule of thumb is never to reveal all your cards during preseason so hopefully we’ve not seen the best Xavi has to offer in 2023/34 just yet. But what exactly have we seen, then?

Let’s have a closer look.

The premise

There are certain things Xavi doesn’t compromise on no matter the system, the players or the opponent. Those are his non-negotiables; aspects of his coaching philosophy he will insist upon game after game, week in, week out. Take the whole verticality issue, for instance. Barcelona have players who invite chaos, running power and dynamism; players like Ousmane Dembele (now gone), Alejandro Balde and Frenkie de Jong. But chaos, running power and dynamism are so ingrained in the way Xavi sees football, those players are just complementary pieces of the steamrolling machine, not the machine itself.

During Barcelona’s three preseason games, we caught a glimpse of Xavi’s non-negotiables once more. In every game, without exception, Barcelona looked to do similar - if not the very same - things over and over again. For better or worse.

Most of what I’ll talk about concerns the build-up phase for a simple reason: the first - and to an extent, the second - phase of the game is where Barcelona are most consistent and this is where most of the repeatable actions and robotic patterns can be discerned. And contrary to popular belief, robotic is good in this instance. It’s good because it suggests a coachable aspect of the team; something that’s a learned behaviour rather than instinct or individualism. So what are those patterns, then?

Xavi’s (build-up) non-negotiables are:

- +1 rule of numerical superiority

- Triangles, triangles and more triangles

- Wall passes and third-man sequences

- Deep carries

In essence, this is how Barcelona operate in almost every scenario. It’s repetitive, steady and reliable. But, to an extent, it’s also predictable. On the other side of the coin, however, are things that seem to be a part of Xavi’s tactical identity but are more prone to change; they’re not set in stone. In other words, they are not non-negotiable but rather far more ambiguous.

Xavi’s ambiguities (for now) are:

- Man-marking

- Final third attacking patterns

- System preference

Let’s dissect them further.

Xavi’s non-negotiables

Considering the very fluid and dynamic nature of Barcelona’s current system, it doesn’t surprise that most of Xavi’s non-negotiables are present in the build-up phase. As mentioned earlier, this is the most stable phase of their tactical identity and as such it offers the most recognisable patterns.

Let’s start with the essentials: the +1 rule. By now, this has been well documented and we know Xavi’s positional mind gravitates towards establishing and exploiting superiorities. In this instance, we are talking about ensuring the team always has at least one more player than the opposition in a given area.

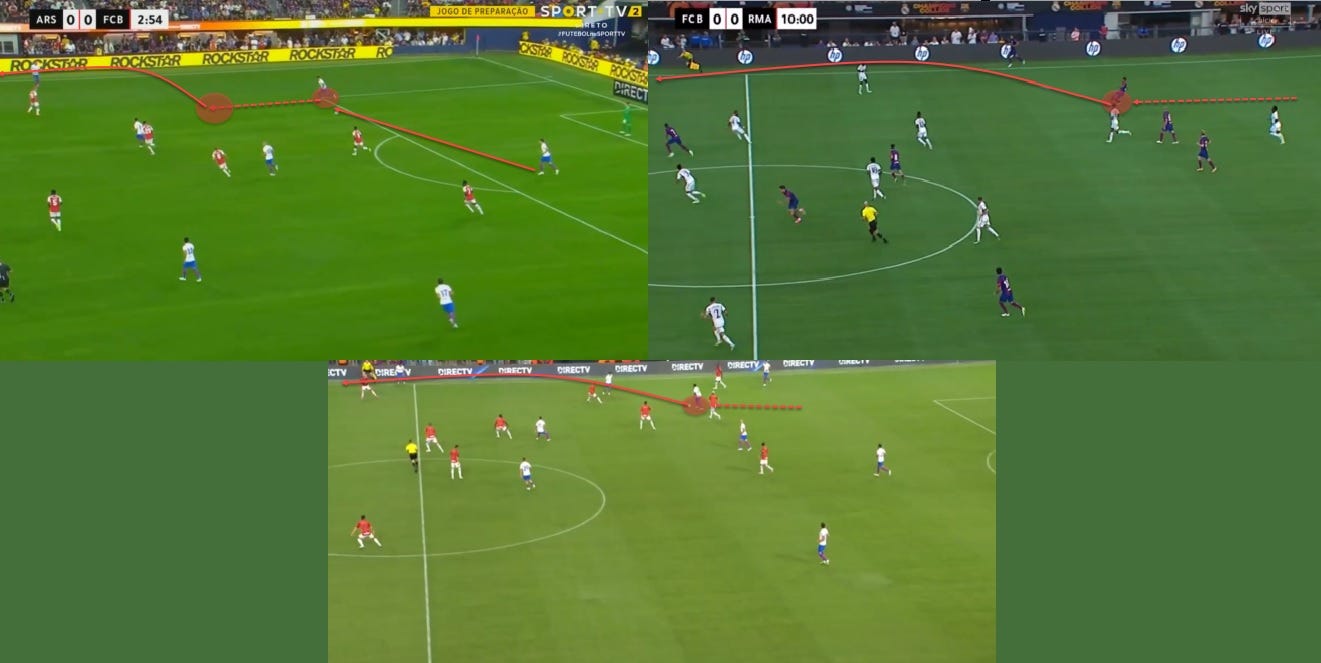

The exact way this is accomplished varies from opponent to opponent, as we can see in all three of Barcelona’s preseason games, but the principle remains: (at least) +1 at all times. Both Arsenal and AC Milan often pressed the Catalans’ backline with a single player, meaning the centre-back pairing was enough to establish superiority.

If, however, the opposition presses with two (or more), the structure changes to accommodate it. Real Madrid, for example, defended in a flat 4-4-2 which forced Barcelona to adapt, often dropping De Jong into or just ahead of the backline, similar to what Busquets had done for years at the club. This is a basic concept many coaches and teams use and it’s something Xavi has been using throughout his tenure.

For that reason, as it was a staple in years prior and now in preseason too, there’s reason to believe this is indeed a non-negotiable and will remain a rough constant in Barcelona’s identity. The same can be said for triangles, something Xavi is adamant about.

Triangles are another basic component of positional play as they allow easier link-up. In other words, they give the ball-carrier options and ensure the players are well-connected on the pitch. But it’s not just that. Triangles are essential for Barcelona’s progression tools from the deep areas.

The player at the tip of the triangle is often the one used as part of a wall pass or a third-man sequence. Essentially, they will be used as a lay-off option to access the free man whose existence was ensured by the previous aspect, the +1 rule. If that rule guarantees Barcelona always have an option of an unmarked player, the wall pass/third-man sequence in turn ensures that option can be reached.

The sequence would then go as follows: a deep ball carrier accesses a dropping option from a higher position who then lays the ball off to the free third party, usually out on the side.

There is a saying that states when executed properly, the third-man concept is undefendable. We can see its effects in the example above. Accessing the third man in that passing sequence is easy because that free player always either has a dynamic advantage - meaning he’s on the move before his marker - or positional advantage - meaning he’s in a superior position or has control of a certain position over his marker.

This goes hand-in-hand with the other two concepts, solidifying Xavi’s need for achieving superiorities, which is possible through his non-negotiables. There are more of them, however; some are more prominent than others. Deep progressions and long distributions certainly seem like a big part of Xavi’s philosophy.

Even more interesting is the fact that the other three aspects enable them in the first place.

Xavi loves for his backline to progress the ball by breaking the lines via passing, yes, but carrying seems even more prioritised. It does make sense, even if it’s inherently riskier. Carries are far more effective in destabilising defensive structures because they force the opposition’s markers to leave their position in order to collapse on the carrier.

This inevitably creates space somewhere else and a risky carry is then rewarded with a free man somewhere else on the pitch. Barcelona use this for their long distributions a lot. Often, the centre-backs, if they are the free man in a given sequence, will be instructed to run with the ball and then aim for runners higher up.

We can see three such examples above, one from each of the three preseason games. But there’s more to this than just aiming to exploit space. Ideally, Barcelona want to progress systematically; slower, sure, but steadier and more consistent. However, that’s not always possible and in such situations, the deep carry into a long distribution sequence will be used to skip the entire second phase of the game and establish a position in the final third.

This works well against highly man-marking-oriented teams who won’t leave much room to create or access the free man. In those cases, Barcelona almost exclusively go long, either directly from the backline or they recycle out wide and then utilise the overload-to-isolate tactic, another staple in Xavi’s repertoire.

Subscribed

Xavi’s ambiguities

The further up the pitch we go, the more open to interpretation Xavi’s tactics become. While the build-up was comparatively void of improvisation, the final third tools and off-the-ball structures are (somewhat) different. Of course, Barcelona are still a very man-marking-focused team defensively; throughout Xavi’s tenure, this has been both his great instrument and his bane.

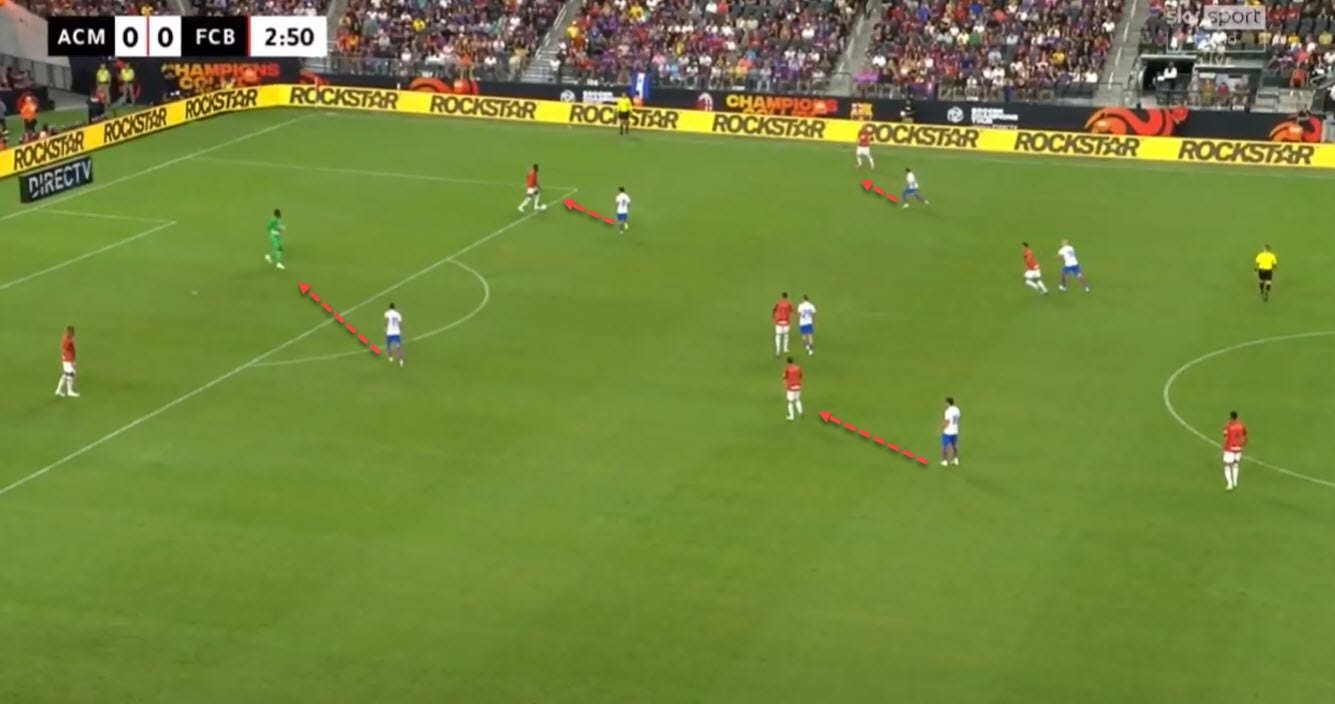

During the preseason, not much seemed to have changed; Barcelona were still man-oriented when hunting for recoveries and the opposition were more or less successful at exploiting it depending on their own technical and tactical qualities. In that sense, this is still a non-negotiable.

However, with the introduction of both Oriol Romeu, a player more astute in defending space rather than marking the man, and Ilkay Gundogan, a physically declining player whose legs may not accommodate such a tactic, something is bound to give. In fact, we saw glimpses of a more hybrid structure in defence throughout the preseason.

Yes, when pressing high, Barcelona were still man-oriented, as seen above, but in deeper mid-to-low blocks, those priorities seem to have changed at times. The structure was more zonal, meaning every player was in charge of defending the area where he was positioned and would deal with any potential threats accordingly, if and when they entered his zone.

For now, it’s very difficult to say whether we can expect to see more of that moving forward but there is reason to believe that may be the case. Generally, however, zonal marking is regarded as the more difficult one to master compared to man-marking but with a higher ceiling overall. In other words, it would be a bigger test for Xavi’s coaching know-how. But it doesn’t stop there either. Xavi’s Barcelona are known to be (overly) vertical and that identity mirrors their coach’s own as a player to an extent. However, part of the verticality issue stems from their chaotic defensive mechanisms.

Essentially, the more spent and more aggressive a team is off the ball, the more difficult it is for them to instil calm and security immediately upon recovering possession. Not only is it a physical toll which requires insane fitness levels to sustain - therefore limiting what one can do on a technical/retention level following the recovery - but it also requires an entirely different mindset in each of the phases respectively.

Players are in a highly aggressive and chaotic state of mind when engaging in such duels off the ball while the requirements following a successful defensive phase are the exact opposite. It’s a sudden shift not many can consistently execute. And inconsistency in one aspect breads inconsistency in the other. Meaning, the more duels you have to engage in, the less technically sound you are and the less technically sound you are, the more duels you need to engage in. It’s a vicious cycle which dilutes the team’s ability to control a game.

Another point of uncertainty is the final third efficiency. The overload-to-isolate tactic is prominent here too as a long switch into an isolated winger often starts the attack and Barcelona immediately turn on the offensive.

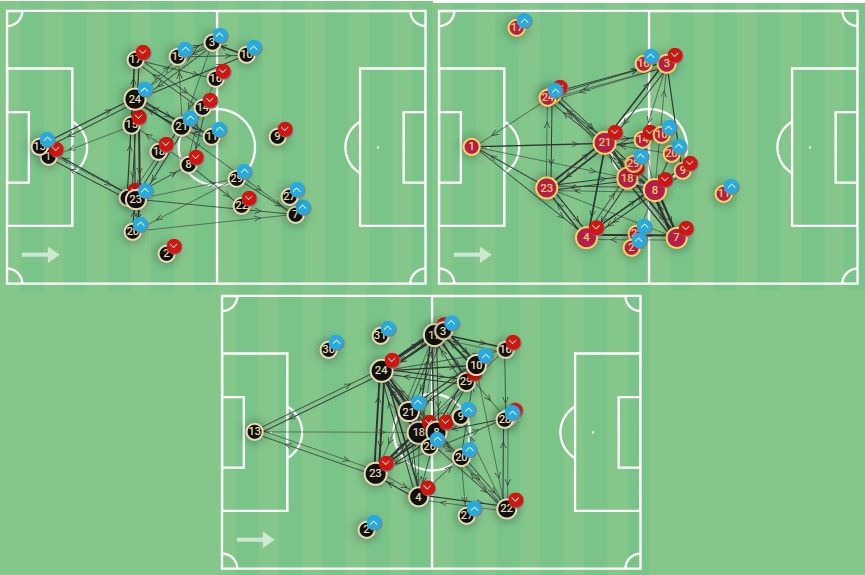

You can see it in all three of Barcelona’s preseason pass maps; they are always skewed towards one side of the pitch. This used to mainly be the left but with the departure of Dembele and the rise of Balde as the great outlet, the left could now also be seen as the isolated side moving forward. Either way, this is a prominent part of both the build-up play, albeit one that often skips an entire phase, and the final third sequence, which is highly vertical and direct too.

Of course, Dembele’s exit is a point of interest here as well since it voids Barcelona of their best space exploiter. Balde can be the replacement but with a different final third repertoire. Similarly, Raphinha is an option but he remains someone better utilised in a minimum-width setup rather than being forced to cover a lot of ground and sticking to wide positions. All of that puts this aspect under question, meaning it dances on the edge of the non-negotiable category.

But this is true of most of Barcelona’s attacking tools. Essentially, there isn’t much here in terms of clear robotic sequences; no learned behaviour as such or no real patterns. Even the systems themselves are somewhat unclear. Everything points towards the return of the box, yes, but we have seen both that and the classic 4-3-3 in preseason. But in this context, variety is good.

That said, there are some certainties in the final third, though:

- Half-space penetrators

- Combinatory striker(s)

Both aspects are complementary too; one enables the other. As a general rule of thumb, Xavi doesn’t force his strikers to attack space as much, instead opting for a more combinatory role that can help eject other runners from the team. That role usually falls on the shoulders of either Barcelona’s high interiors (number 8s) or their outlets (wingers, full-backs).

We can see that here, too. The striker drops deeper and that immediately prompts runners on either side of him. This can be done with any combination of the runners mentioned earlier; the execution remains similar. It has to be noted, however, that Robert Lewandowski tends to drop deep and stay there longer, registering more touches and often trying to either outplay the opponent or win a foul while someone like Ferran Torres drops, plays a simple lay-off and then bursts back into space.

There is a clear difference between the two profiles and this gives Xavi more margin for variety, albeit with a similar outcome regardless of who dons the number 9 role. But even with some certainties mentioned here, the loss of Dembele, the absence of robotic patterns and Barcelona’s remaining activity in the transfer window mean their final third dynamics are very much an uncertainty at this point.

Will that remain to be true once the season starts? Only time will tell.

Final remarks

The preseason gives us a glimpse of what is to come in the near future. Nothing more and nothing less. At the end of the day, it is just that - a glimpse. But while it is true we shouldn’t make any conclusions solely based on three friendly games, it’s still interesting to dissect them and see what - if anything - has already changed.

Most coaches don’t reveal much in preseason. And they shouldn’t. But whether they like it or not, some aspects of their tactical identity always slip through the cracks. Even if it’s only for a second.

And once they do, we’re here to spot them.