Raphinha & the annihilation of the offside line

Raphinha is the master of the parallel run and we’ve already seen him reap the benefits of its (almost) unstoppable nature.

Barcelona wrote history in Pamplona by managing to come back from a deficit in a numerically inferior position on the pitch. Down to 10 men, your best player red-carded after just half an hour of play and the home side fired up like never before after going 1:0 up. By all means, a recipe for disaster. But despite a clearly insufficient first half, Barcelona clawed their way back to victory, saved by Pedri’s sensational hit and Raphinha’s brilliant header.

But interestingly enough, despite both of those moments being of the utmost quality, it’s something else that caught my eye again. Raphinha’s goal was the carbon copy of the one he scored for Brazil against Tunisia in September and it wasn’t just the header that mattered either. It was the movement prior to that.

The best forwards or goal-scorers move better than the rest. It’s as simple as that. Of course, there’s a lot more than goes into it but the movement of elite forwards is what often separates them from the rest. And being able to manipulate the offside line is a huge part of that. In football, even though it’s sometimes a concept non-fans have trouble grasping, offside is a relatively simple term within a relatively scarce concept. How so? Well, in football, how often do we get offside situations per game? Perhaps a dozen times throughout the full 90 minutes of a match. And often enough, a dozen would be regarded as a lot. Still, it’s one of the regular obstacles a forward will face on his way to rattling the inside of the opposition’s net.

But what if I told you there is a sport whose very essence lies in the perpetual state of the offside line? A sport in which beating the offside line is not only beneficial but also essential? That sport is rugby or more precisely, the Rugby League.

Rugby & the weapons against the offside line

In rugby, the players have to be in constant motion to even have the slightest chance of beating an offside line and in rugby, getting caught offside is a much larger infraction than just having to stop the attack. Are you in front of a teammate who is carrying the ball or who last played it in open play? Offside. Are you, from that same position, interfering with the play in any way? Offside. Are you moving forwards from that same position towards the ball? Yup, you guessed it - offside.

These are the simplest examples that are also applicable to football situations. But the rules get exponentially more convoluted the deeper you go into the other aspects of the game. Set pieces, rucks, scrums, lineouts and accidental offsides all have their different set of rules. The list, honestly, seems endless and if seasoned rugby analysts and coaches still have disputes over it with decades of experience under their belts, I’m not even going to try and go into it any deeper.

The bottom line is, getting caught offside in rugby is a clear violation and is treated as such under the right circumstances. Sanctions range from being awarded a penalty at the place of infringement to initiating a scrum where the offending team last played the ball. Either way, it gives an instant advantage to the other team and therefore, the efforts put into avoiding such situations are much bigger. This is where football can learn a lot from rugby.

Unlike in football, the reference here is the ball. The main difference is your teammates can’t receive the ball (or otherwise interfere with the play) if they are ahead of the ball at the moment of passing. This means a pass is never forward but rather always sideways or backward. In other words, the offside line is determined by the position of the ball rather than the position of the opposition’s defensive line. This is what makes it so dynamic and so, so difficult to master. Perpetual movement.

So how do rugby players bypass or manipulate the offside line? In its essence, one of my favourite solutions is simple. How do I ensure I’ll win the duel against the defender? Or rather, how do I ensure I enter the challenge with the tides already heavily tilted in my favour? The answer is velocity. But not any kind of velocity. Maximum velocity. Top speed. A full-tilt sprint. This is the concept at the crux of our issue.

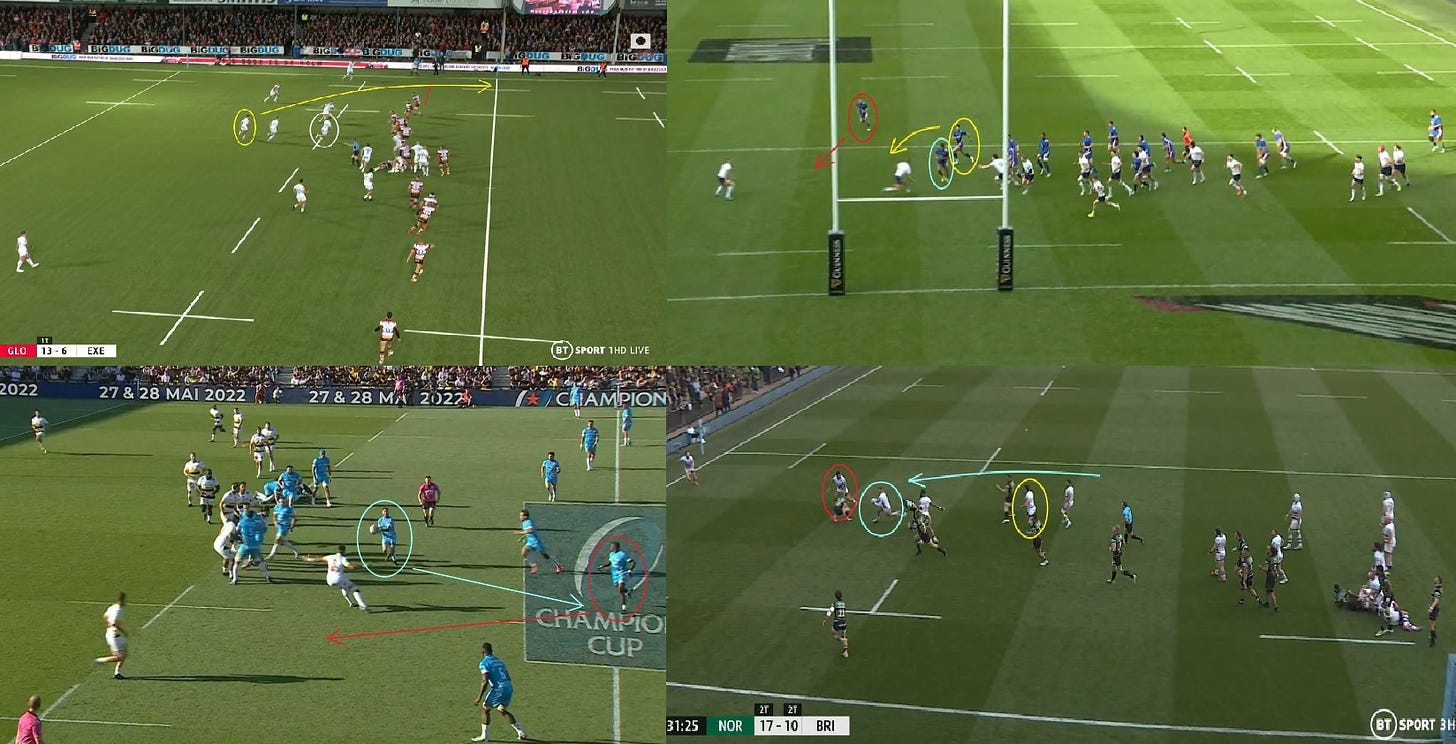

In rugby, this is achieved via something we can simply call the ‘parallel run.’ The idea is to a) run parallel to the offside line until top velocity is reached and b) turn into space instead of driving off into space. What’s the difference? Well, turning is much faster than driving off. With the former, you’re already sprinting while with the latter, you just rely on the explosiveness of your start. In all the examples above, you see the eventual ball receiver is already sprinting or at the very least starting to sprint before the pass is played into him.

That not only ensures he gains a head start over the opposition but also makes his ball-handling much easier since there is no need to further accelerate nor maintain that top velocity as the separation will have been made by that point already.

In this example once more, the ball receiver reaches top speed even before the ball is passed into him. He runs parallel to the offside line, building up velocity, and then receives on the edge of that same line. This ensures he will go charging past the defenders who rely on the explosiveness of their drive-off from a standstill position. Of course, in rugby, all of this is made even more difficult by the fact the defender can just tackle you to the ground. If you want to learn more about rugby, I highly recommend visiting Total Football Analysis’ TotalRugbyAnalysis website where my esteemed colleague David Astill is doing some fantastic work.

Now, the million-dollar question remains: how do we translate this to football? And what does Raphinha have to do with all of it?

Let me explain.

‘The Raphinha’

When people think of Raphinha, they mostly think of his dribbling or the trademark inswinging delivery. That, of course, is what comprises a part of his profile. But while you could argue there is a certain narrowness to the player, Raphinha is more than just that. What fascinates me most about him, however, is his movement.

The Brazilian is undeniably quick, agile and explosive, meaning using him as an outlet is a viable option. In fact, we’ve seen that side of him time and again for both Leeds United and Barcelona. But it’s the more technical nature of his movement that stands out the most. Not exactly the what but the how. Raphinha moves fast, yes, but he also moves smartly and that’s his greatest weapon. It’s also why despite two ridiculous FIFA-like headers against Osasuna and Tunisia respectively, I was infinitely more impressed by the movement that preceded both. When you pair that up with his natural goal-scoring instincts and ball-striking, you get a deadly forward.

But let’s get back to rugby and the two goals I keep mentioning. Raphinha is the master of the parallel run and we’ve already seen him reap the benefits of its (almost) unstoppable nature. In football, as opposed to rugby, players usually beat the offside trap by playing off the shoulder of the defender, utilising the blindside, perfecting their timing and abusing their ridiculous explosiveness (should they have it in the first place). All of these are fine if utilised well but they can also be suboptimal. Why? Well, mainly because they rely on perfection to be executed well. There’s nothing wrong with relying on your reaction time beating the defender’s as long as it consistently yields results. There’s also nothing wrong with playing off the shoulder of defenders either if you exploit the blindside well and can explode into space quickly. But the parallel run eliminates the need for such perfection.

It essentially guarantees you get a head start on your marker, removing the need for inch-perfect execution. In order for the offside trap to work, the defensive line needs to be stationary or at the very least, stay on the same line at all times. Otherwise, it won’t work. But that also means there is no way for the defender to match the velocity of the incoming forward if he’s running parallel to the line in order to ramp up speed. Take Raphinha’s goal against Tunisia as our first example.

The Brazilian’s acceleration is impressive and partly, this gives him the edge in the ‘race’. However, it’s the curvature of the run that ensures he wins it. Instead of running straight into the space behind the opposition’s line, he first accelerates parallel with it, ramps up speed and then turns into space. That’s the key - turning into space, not driving off into space.

Notice that at the moment he receives the pass, he’s already ahead of the defender as the separation had been created and ensured by the parallel run beforehand. The defender here is also in a very ungrateful position, one that I’m still trying to figure out how to approach. There is no way he can match the speed of the forward from his standstill position. And to maintain the offside trap, he also needs to remain (more or less) stationary. If the idea is to win the foot race, the defender would need to do a similar type of movement but that also almost guarantees the offside trap is broken. Even still, he operates within a far more limited zone compared to the forward.

Raphinha can curve his run or simply run parallel to the defenders while his markers don’t have such leisure. If executed well - which isn’t as complex as it may seem - it almost renders the offside line obsolete. Almost.

Now we come to the game-winning goal against Osasuna. The eerie similarity between the two goals is absurd and honestly, a bit frightening. But at the same time, knowing what we know now, it’s also not that surprising. Raphinha is simply following the same blueprint, the same technique and the same chain of events to ensure this action is a carbon copy of the one against Tunisia. And it works.

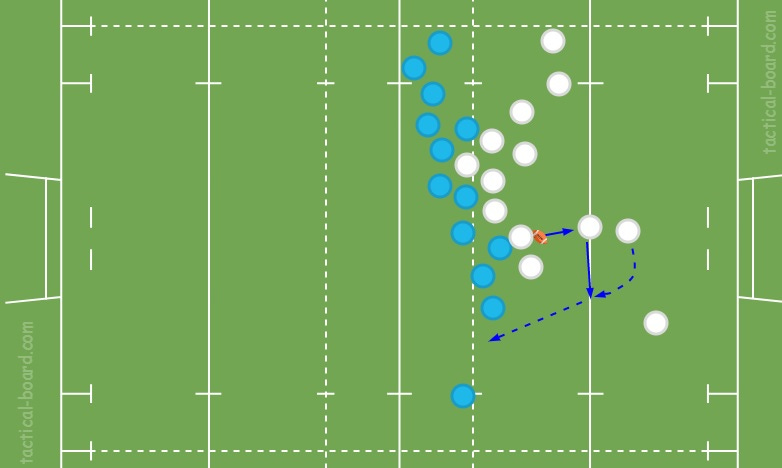

Again, the run is curved. Again, top velocity is reached before the space is attacked. Again, he turns rather than drives off. And again, he scores in an identical manner. Equally impressive, equally unstoppable. Let’s consult the tactics board one more time for more clarity on the nature of this move.

Building velocity by running parallel to the line, turning into space the moment the pass is deployed and creating separation through (often) unmatchable head start. When you combine those factors into one sequence, it leaves the defence with little chance of retaliation.

A movement worthy of all the three points it ultimately secured for Barcelona. And of course, what a glorious header to finish it off.

Final remarks

Raphinha isn’t the only player capable of executing this move. In fact, we’ve seen Ansu Fati do the same on one occasion this season and players like Kylian Mbappé do a variation of it to consistently beat the offside line. However, the true parallel run is still, to a certain extent, a rarity in football despite its relatively ‘easy’ nature of execution.

It would be an exaggeration to say Raphinha has killed the offside line but he has certainly made it far easier to bypass. As of right now, there is no clear antidote for this move and seeing the Brazilian has mastered its venomous bite, we can rightfully call it ‘The Raphinha’.

He’s earned as much and it remains to be seen how the recent turn of events influences Xavi’s selection going forward. Maybe there’s a shape-up on the cards. And it’s getting difficult to argue against it at this point.