Should Barcelona go all out for Julian Nagelsmann?

Clubs under Nagelsmann play attacking football and dominate their opposition, a philosophy that mirrors Barcelona's view of the beautiful game. But he is not without faults.

Summer is almost upon us and with it, so is Xavi's departure from FC Barcelona. The Catalans still have a chance to salvage the season after their triumph against Napoli but the most difficult question of all remains unanswered: who will be the club's next coach?

Will it be Hansi Flick, the direct, instructive and demanding man-manager? Will it be Roberto De Zerbi, the revolutionist? Or will it be someone like Julian Nagelsmann, perhaps the most sought-after coach on the planet? The current Germany manager and former Bayern Munich coach will be on the market after the Euros and if reports are to be believed, he is someone Joan Laporta admires. And why wouldn't he? Nagelsmann is an anomaly in world football.

So, should Barcelona go all out for him?

Manager profile

Julian Nagelsmann is only 36 years old and yet he boasts a CV stronger than most, if not all, candidates for the Barcelona job. He started his football career as a player but injuries meant he could not pursue it for long. That, however, did not stop him from completely immersing himself in the sport; he got his bachelor's degree in sports and training science, acquired his professional coaching license and started his climb up the ladder as Augbsurg's scout in 2008. Come the summer of that same year, he transitioned to an assistant coach role at TSV 1860's youth team, staying there until 2010 when he jumped ship to Hoffenheim U17, first as assistant manager but then, soon, as the lead coach outright. And this is where the story truly begins.

At the time of his appointment, Nagelsmann was only 28 and Hoffenheim were rotting in 17th place, in line to be relegated soon. But the young coach had different plans. By the end of the season, he had brought them to safety and then, rapidly moved them up the table in the coming years, turning a relegation-bound team into Champions League participants. Hoffenheim's resurgence was followed by RB Leipzig's, where he took a decent squad to the 2019/20 Champions League semi-finals and made the world stand up in awe. Finally came the well-deserved Bayern Munich job.

Despite that probably being the least impressive stint of his colourful career, Nagelsmann still won three trophies in Bavaria, claiming a Bundesliga title and two German Super Cups. In total, he has already coached in 393 games, winning 223, drawing 90 and losing 80 matches, good enough for 1.93 points per game. But all of that is derived from his unique outlook on football and a mind almost like no other in the industry.

The goal is to strive for perfection, but you'll never achieve it. When you're completely familiar with a basic formation, doing everything right, you can then rehearse a new basic formation and try to consolidate the processes in such a way that they're almost perfect again. There are always nuances, developments and things you should improve. I would find it rather frustrating if you could no longer optimise anything. The job would then be less fun. Challenges are important in life, to grow from them.

And this is what Nagelsmann is all about — constant optimisation. The young coach will tweak his system as much as he needs to win and exploit his opponent's weaknesses. In that sense, perfection is never achieved because being perfect would mean stopping, standing still, and not pushing yourself to become even better. For Nagelsmann, that is not an option. This is akin to the coaches who inspired him the most: Pep Guardiola, Thomas Tuchel and even a hint of Arsene Wenger.

But in this whirlwind of constant change lies a deep-rooted foundation of principles; principles that remain solid and unchanged; principles that are unyielding and uncompromising. In his own words: 'They always apply, no matter what the score is, who the opponents are or who is playing.' And that matters; tactics are tweakable, principles are solid.

At the core of his philosophy are four main pillars:

- Innovation

- Adaptation

- Domination

- Relationships

Nagelsmann is a modern coach; one that uses technology and data to improve himself and his players. From operating a big screen during training and consulting the numbers to using a drone to record sessions, the German is embracing modernity in the name of optimisation. That makes him innovative and his tactics fluid and adaptive to the opponent. But at its core is pure domination; Nagelsmann wants to dominate time and space on the pitch and be the protagonist, always.

However, all that comes from the relationships the players form within the system. They are what matters most. They are at the centre of his tactics.

On-the-ball principles

The first basis for deciding is what sort of players you have available. That’s the decisive point. You always base your ideas first on the players, on the category of players we have. That’s the most important factor.

Nagelsmann is a highly positional coach; he believes in controlling space by structured occupation in certain zones of the pitch. By controlling that occupation and having his players dominate their zones, he controls space. But he is also a relationist coach; one that bases his philosophy on the relationships his players form on the pitch. Through that interconnectivity between different profiles within the system, he controls time. By combining both, his teams can truly dominate.

But at all times, these two approaches are at odds with each other in Nagelsmann's mind; depending on which one prevails, his teams are either rigid and heavily structured or far more fluid and free. So over the years, we've seen Nagelsmann's teams that are more systematical or more vertical, more rigid or more free and more positional or more relationist. From Hoffenheim to Leipzig and then to Bayern and Germany, they all shared the same core values but were all, at certain points, very flexible in how they were deployed.

For that reason, it's almost impossible to list a single structure or certain profiles that characterise his teams.

Nagelsmann is not hell-bent on a back-three formation. Similarly, he's not hell-bent on a double pivot or a certain profile next to his #6. He's also not hell-bent on marauding full-backs or strong-foot wingers. All of that can change depending on the context of the game, the opposition or, most importantly, the players at his disposal.

At the beginning of his career, Nagelsmann used to be far more idealistic and pure in his approach, resulting in countless tweaks and tactical machinations. Nowadays, however, with more experience, he is more practical and understands success at an elite level is often found in consistency and how you manage your best players. In that sense, he is perhaps 'less tactical' than he used to be. That, however, is not a bad thing. Not at all.

In general, in the backline, he wants players confident on the ball and great duellers for centre-backs who can defend in a high line. In a back three, the central defender is often the most progressive and the leader of the defence. The ideal pivot for Nagelsmann is the quarterback profile; a player who links defence and attack; an offensively and defensively complete profile. This player, as Nagelsmann has stated in the past, is the most important player for any of his teams.

The full-backs can be more or less aggressive but must be technically secure to participate in the build-up or work in advanced pockets if necessary. The same goes for the inside forwards; they are generally not wide wingers but players comfortable in the half-spaces in a minimum-width setup. Finally, the striker is often involved in open play but has to be prolific in the box too.

While 3-4-3 is certainly a structure we sometimes see from Nagelsmann, his flexibility means it's difficult to pinpoint one specific system he prefers. We've seen him in a 4-2-3-1, a 3-2-5, a 3-1-6, a 4-3-3 and countless more, often interchanging during games and morphing from one shape to the other. Just as the tactics are derived from the players he has, so too is the structure; it's built from the inside out.

30% of coaching is tactics, 70% social competence. Every player is motivated by different things and needs to be addressed accordingly. At this level, the quality of the players at your disposal will ensure that you play well within a good tactical set-up – if the psychological condition is right.

Catering to the players at his disposal and creating a structure that gets the best out of them is what Nagelsmann does now. He still tweaks and tinkers. But it all starts and ends with the players he has at the club. So how would that translate to Barcelona?

Barcelona are in line for a major overhaul this summer with several big exits reportedly on the cards. So predicting who's there come the summer and Nagelsmann's potential appointment is... unenviable. But assuming these are the players he'd have at the club, he'd look to create an environment that works best with the profiles he has, not the other way around. Meaning, instead of creating a system and shoehorning players into it, he would use the players to create the system in the first place.

But even so, some question marks would need to be answered. Barcelona currently don't have a quarterback pivot in the squad and the choice for the left winger is also up for grabs. But given he is not overly fond (or dependant) on pure wingers, it's not ruled out his inside forwards in the frontline could potentially be profiles entirely different than what the Catalans currently have. Half-space dominators like João Felix would fit and obviously, Lamine Yamal would be an option but would see his role slightly tweaked to central corridors.

Nagelsmann would love all three of Pedri, Gavi and Frenkie de Jong but considering none of them are currently in the mould of his ideal 6, it remains to be seen how he'd structure that midfield line. A double pivot would almost certainly be the case, either an outright or a makeshift one created in-game even if it wasn't imagined that way on paper. In a very general sense, Nagelsmann likes to have a physical/defensive presence next to his distributor 6 in a 4-2-3-1 and then a more advanced interior/10 roaming just ahead of them.

The situation is similarly uncertain for Robert Lewandowski in the striker role; he fits the profile but would he be able to execute it at the required level next season, aged 36?

Changes are coming to Barcelona so some of the big names listed here might not be there for Nagelsmann to use. However, his philosophy aligns well with the club's and the profiles of the squad. That alone is a great foundation to build upon.

Build-up tactics

The basic framework has been in place since my first year as head coach at U19 level. The mantra is 'control the game by winning the ball high up the pitch and changing the tempo in possession'

In the public eye, Nagelsmann is a complicated persona. In reality, however, his 'mantra', as he calls it, is quite simple: control. But Nagelsmann's control is more than just leaving the opposition with no say in the game; it's about utterly dominating every aspect of the clash from start to finish. The means for that can be complex and can vary, leaving the impression of convoluted tactical stratagems. What makes it complex is the unpredictability of his approach.

As alluded to earlier, Nagelsmann is a hybrid between a heavy positional and relationist coach; one seeking order and structure but striving for positional freedom and expression for his players at all times. Sometimes, these two approaches can be at odds with each other as going fully in one direction effectively negates the other.

At the beginning of his career and going into his first season at Bayern, Nagelsmann was a clear disciple of the German approach; speed and verticality were at the core of his ideas.

I like to have the ball and I like to attack the opponent very early. It’s always important in my philosophy to speed up the game. If you want to be a good team you have to control all phases. The most important thing is to speed up the game in possession and attack the opponent as fast as possible.

While that is not necessarily true today, glimpses of that Nagelsmann remain. If the chance to exploit space exists or can be manufactured, he will take it and the structure will reflect that intent.

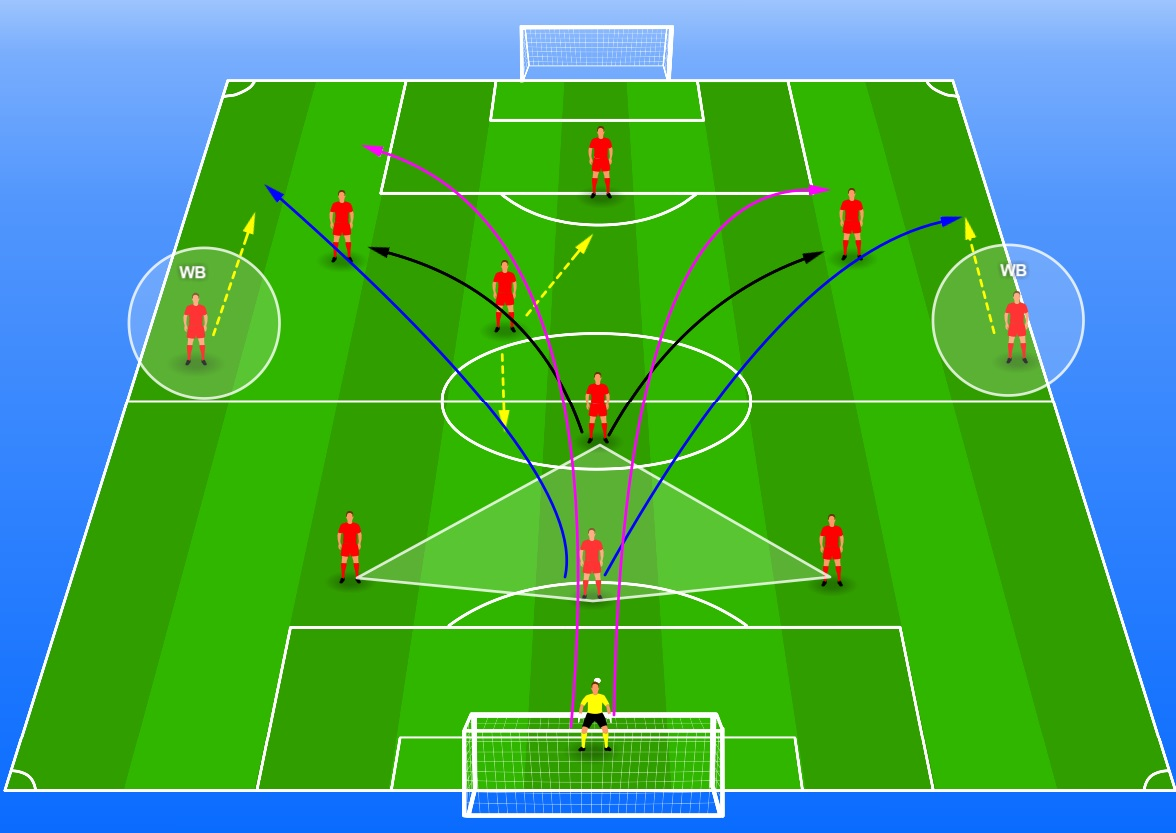

In his first season at Bayern, for instance, Nagelsmann loved the 3-1-6 because it offered him several vertical avenues to explore at all times, giving his distributors targets in advanced areas. The 3-1 in the first phase was the bare minimum, yes, but also often all he needed to execute his plan. That was a heavy positional team; often rigid and often set to control the space. It was heavily positional because the players had predetermined zones to occupy.

This means they were in charge of a certain area and would wait for the ball to come to them instead of going towards it. This lends itself to control of space and efficient verticality as long as the players dominate those predetermined areas and win their battles. Of course, flexibility always exists with Nagelsmann so heavy rotations were possible and welcome.

However, if two players were to rotate, they would have to effectively replicate each other's original roles, meaning if player A and B swap positions, player A needs to be able to execute player B's tasks and vice versa. Otherwise, the positional system falls apart. In other words, all players in a heavy positional system work within a bubble — their zone of influence. Within it, they are free to do as they wish as long as they do their job. They can also replace someone in a different bubble but then have to do the job of the person they are replacing.

The 3-1-6 in particular, or the 3-2-5, were designed with space domination in mind as even a back five would be either outnumbered or at the very least evenly matched against Nagelsmann's attacking force. His teams would widen the pitch, stretch the opposition and then attack depth with ferocity.

In such systems, the full-backs were minimally involved in the build-up and would instead push high and attack spaces in behind. The 3-1 aimed to have the distributors deeper and the rest occupying predetermined spaces in the final third, offering clear vertical options. Joshua Kimmich, the player in the critical pivot position in Nagelsmann's system, was thus the main link between defence and attack.

Standing at the tip of the 3-1 base, Kimmich was an orchestrator; a metronome through whom the game flew. In that lone role just ahead of the backline, he would be in a prime position to receive and then create from, often being set up by dropping interiors who would bounce passes back to him, finding him in positions facing the opponent's goal. From there, Bayern would play forward with speed.

But while Nagelsmann believes in order within the system, he doesn't fully invest in the positional ideology as his teams don't always conform to the stereotypical positional play principles of width, depth and even those predetermined zones of occupation. This is where the relationist side of his persona kicks in.

Somewhere along the way, Nagelsmann realised the best way to get the most out of his players was to let them interact as much as possible; they became the system. Instead of having predetermined zones, he encouraged the players to move as they saw fit in any given situation, letting them forge relationships and interactions and, in turn, reap the most out of their individual traits and raw talent.

Rather than the heavy positional system organised by positions (or zones), Nagelsmann cultivated a system organised by roles — the players controlled their movement, their relationships, and the timing of their actions, achieving the same control he wanted but achieving it through different means. And one way to cultivate interaction and responsibility was through the core principle of compactness.

We play closer together. We rely on each other so we can give the game more speed. If we play more spaced out, we can’t play as fast as the coach wants us to. That’s why we want to play as close together as possible, almost like Five-a-side Footbal. The smaller the space, the better, because the ball moves faster. We attract more rivals that way, but we need to know how to play under pressure. If we succeed, we open bigger spaces and we’re able to attack with more depth. Dani Olmo

While a positional system limits the natural expression of a player's talent, the relationist system reinforces it. Suddenly, instead of a rigid 3-1-6, Nagelsmann involved four, five or six players in Bayern's build-up phase, creating a slower but far more systematic first phase built on as much interaction as possible before exploding forward in true German football fashion. The full-backs would not be exclusively wing-backs but would support the backline, the pivot was often joined by a dropping interior and the centre-backs were encouraged to pick the close options rather than going long. All of it was founded on relationist principles.

This is where the 3-2-5 comes in and iterations of 4-2-2-2. Suddenly, the full-backs would stay deep or even invert to make a back three and Bayern started building their attacks in asymmetrical shapes, especially if the former was the case. Occasionally, that would still mean a 3-1 base in the first phase but since players were given much more freedom to move and interact, they moved more as a coherent unit, forging links and controlling space and time before attacking ruthlessly.

So what does all of that mean for Nagelsmann's tactical approach? It means it varies; Nagelsmann can be vertical. Nagelsmann can be systematic. Nagelsmann can be heavily positional. Nagelsmann can be a relationist. Nagelsmann can be whatever he needs to be to win; it all comes down to what he deems necessary in any given moment and of course, it depends on the players he has at his disposal. It all starts and ends with them.

I learned how to communicate with the leading players and let them take part in my ideas. […] I’ve been on the phone with several players during vacation. I told them about what I want to adapt: more focus on ourselves and less on the opponent. I also asked for feedback from them. […] Maybe I underestimated that face-to-face conversations are more important for some players than I would have imagined as a coach. The players have to feel that they’re being noticed by the coach.

Nagelsmann's team selection tells you a lot about what he wants to do and what he believes is the best way to dismantle the opposition. If he starts a back three made out of three centre-backs, he will likely deploy wingbacks who will be minimally involved in the build-up phase, thus likely giving the team a vertical nature and injecting speed into their system. In that case, we're likely to see a more positional 3-1 base.

On the other hand, if full-back profiles are full-backs on paper too, they will be more involved in the build-up and the team will likely assume a 4-1, 4-2 or a 3-2 base. This will lend itself nicely to a slower but more systemic build-up phase. The complexity of Nagelsmann comes in guessing which one he'll go for. If he deems his team good enough and individual raw talent of a high enough level, he will likely create an environment that cultivates exactly that.

If, on the other hand, his back is against the wall, Nagelsmann often reverts to a more rigid but also more controllable positional system. Over the years, he's learned to be 'less tactical' and more 'pragmatic', meaning he understands tinkering too much and being too complex can sometimes hurt you in elite football. Instead, as long as you can get the best out of your best players, you can thrive.

The brunt of that thriving success, however, comes in the final third.

Final third tactics

I demand an active style of play and to do that you have to maintain a certain closeness to the football. (...) Fundamentally, it’s about taking up a position in attack so that you can be passed to if the ball is moved around, but also such that you’re close enough to the opponent to initiate the gegenpress if we lose the ball.

Nagelsmann is the attack-first type of coach; he ensures the team is dominating the opposition in possession of the ball and can force them into submission. And just as was the case in the build-up phase, his final third tactics are based on the same core principles such as compactness and establishing the system on the players first.

But there is more complexity to his approach than just these two aspects. Nagelsmann's football is founded on dynamic movement between the lines, enhancing the players' raw talent and most of all, his football demands closeness and compactness.

In the final third, Nagelsmann's teams will generally be close to each other, allowing for short and fast ball circulation with an emphasis on outplaying the opposition. This goes hand in hand with the relationist aspect of Nagelsmann's coach profile as the players are closer together in a compact unit, fostering the relationships between them and encouraging constant interaction and adaptation.

It's difficult to pinpoint certain patterns since those change almost at all times for the German coach. However, we can identify certain fundamental aspects which seem to be a constant, like less crossing, less emphasis on 1v1s out wide and more focus on central overloads and combination play, effectively controlling where the play is generated and where potential losses may occur as well.

So a typical sequence under Nagelsmann could include his wingbacks being positioned wider in the second line or advancing higher from those positions and using the midfield overload to recycle the ball into them. They would then carry the ball into space before rotating back centrally to access the narrow front three or the 10s who attack the box.

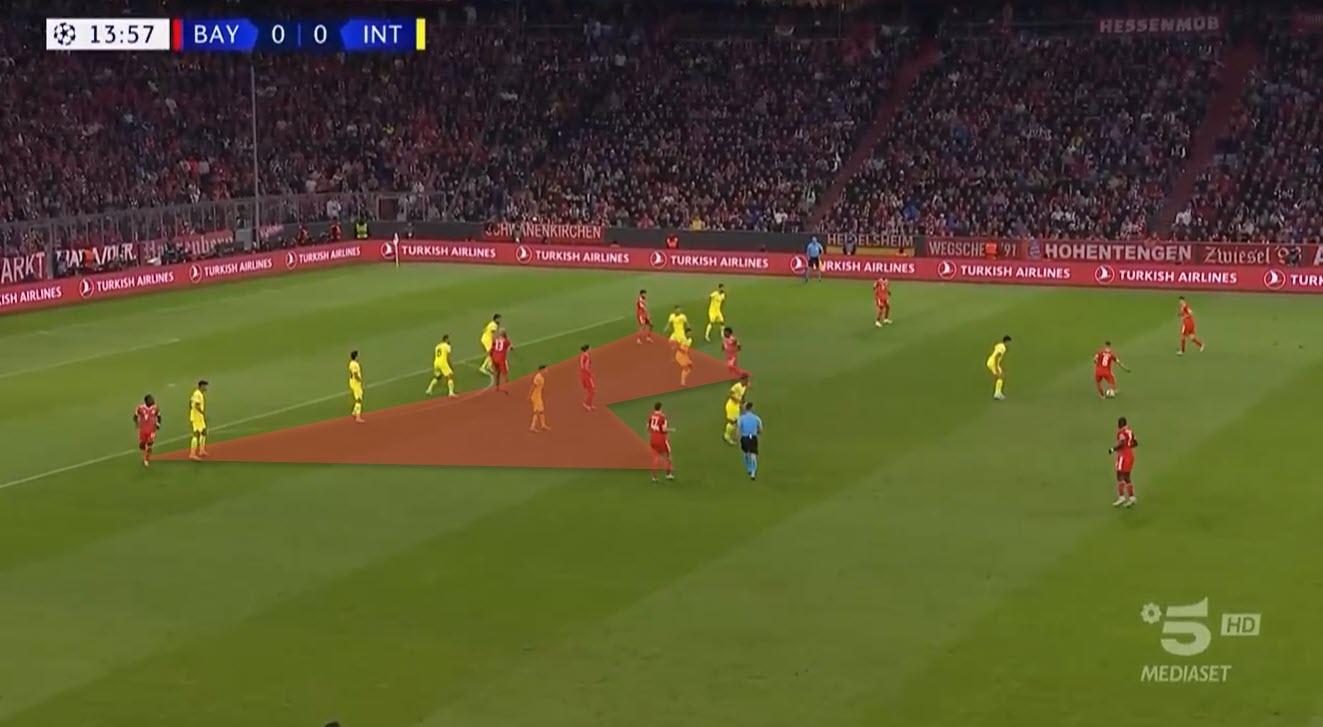

You can see this compact unit in the image above; Bayern under Nagelsmann created central overloads in the final third and would tend to play through the opponent using their technical and tactical superiority. In fact, in Flick's last season, Bayern were first for crosses per 90 at 24.4 while In Nagelsmann's first, they immediately dropped to fifth at 19.3 per every 90 minutes. In the second season, the downward trend continued as Bayern dropped to 10th with only 16.6 crosses per 90 minutes. The emphasis had successfully been shifted towards a different approach.

It's not that Nagelsmann doesn't want to exploit space quickly or vertically; he certainly does. His build-up phase can still be direct and he will create overloads on one side of the pitch to isolate his wide players on the other but often, he will decide to play down the overloaded side or through the congested area rather than eject runners into space.

One of the reasons why is that he often doesn't even use traditional wingers at all. Throughout his career, he would prefer players comfortable in the half-spaces and between the lines rather than traditional width-holders. And even if he had width-holders, often it would be in asymmetrical shapes with only one player acting as a winger while the other was more tucked in. This is where his love for relative width comes into play.

Nagelsmann's widest attackers in the frontline often hug the 18-yard box and the coach hopes to achieve several things with such a setup: 1) Reduce the distance between the players, emphasising interaction and creation of relationships and ease of ball retention, 2) Reducing the distance between his attackers and the goal, 3) Have more players in or close to the box and 4) Reduce the distance players have to cover in case of a turnover, increasing the effectiveness of counter-pressing.

Nagelsmann once said: 'I like to see us shrink the pitch and create overloads near the goal. The rules of football dictate that that’s in the centre of the pitch, so I like to see us have a strong presence in those areas.' so let's focus on aspect number three for a second.

According to the German coach, flooding the penalty area and having a strong central presence has both offensive and defensive implications. First and foremost, it gives his distributors more targets to aim for in the box. Secondly, even if the targets aren't accessed, more bodies give you a better chance of getting to the rebound first. Finally, defensively, it forces the opposition to drop more players deeper, thus giving them less power in a potential transition.

For those reasons, Nagelsmann's teams will often flood the box with five or six players, sometimes even more, and hope to completely overwhelm the opposition. So even if Bayern were to lose the ball in these situations, they would lose it in heavily crowded areas which theoretically gives them a better chance to regain the ball immediately afterwards.

This is a great segue into the final section of our tactical analysis: defending.

Off-the-ball principles

We want to have good stability. There are moments when we want to give the opponents less room. We want to defend high, but also leave less space in behind our defence. (...) a good defence is important. We want to be more dominant in the game to reduce the time we have to defend for.

With Nagelsmann, the best form of defence is attack. In other words, he prefers to defend with the ball and then use that solid in-possession structure to smoothly transition to defending if and when the ball is lost. Again, the core principle of compactness is crucial here because it ensures his players are close to each other, making the counter-pressing easier and more successful.

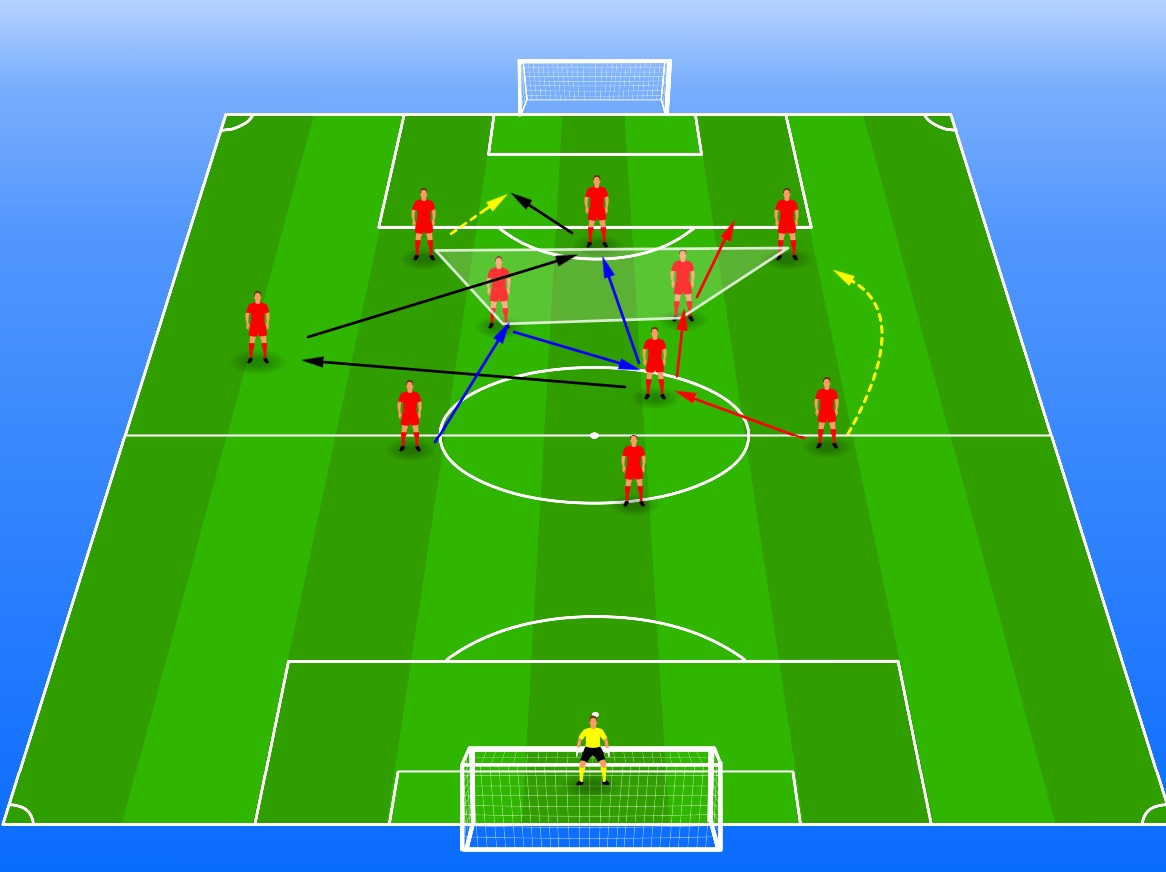

The high press remains a staple in his tactics and it's also one of the things we almost always see from Nagelsmann's teams. The general setup is a largely man-marking scheme with certain pressing triggers such as a pass into the wide channels, either to a wide centre-back or a full-back, which banks on using the line as an additional man in defence.

Above is an example from Bayern Munich's game against Barcelona and a sequence depicting a successful high press initiated by a pressing trap out wide. As soon as Barcelona tried to play out of the back using the wide channels, it activated the Bavarians' press, mirroring their shape and collapsing quickly on the wide men.

A couple of things are worth noting here: once their press is activated, Nagelsmann's teams will use a man-marking scheme and will press religiously and with a lot of intensity. This does mean a fair bit of athleticism is often needed but since compactness is non-negotiable, the distances between each player are shorter and thus require less coverage.

Intriguingly, a good rest defence is paramount for Nagelsmann and often, we'd see his teams in different in-possession shapes due to a variety of structures the German coach deploys. However, in general, a 3-2/3-1 base would be the go-to option and often proved enough. One aspect Nagelsmann shares with some of the best but also often most aggressive defensive coaches in Europe is the intense deployment of full-backs off the ball.

To properly pin the opposition down and dominate the space they operate in, Nagelsmann would instruct his full-backs to push high up the pitch in the defensive phase, following their markers as deep as their own box when counter-pressing. This is effective because of the pinning aspect but is also a big chance-creation tool. But it isn't just the full-backs who are instructed to be aggressive.

Nagelsmann's compact and aggressive approach to front-footed defending ensures his teams can quickly flood the box following a high turnover, as can be seen from the example above. This, again, goes hand-in-hand with the previous principle of crowding the central zones and zones near the goal we discussed in the previous section of this tactical analysis.

All of that being said, however, weaknesses still exist and mostly pertain to teams successfully exploiting this aggression and using it against Nagelsmann's teams. Teams who had the means to explode forward with pace and intent could find joy in Bayern's wide areas should they break the first line of the Bavarians' press.

Since the full-backs were often high up following their markers, space would appear behind them and it would be the wide centre-backs' task to cover it as quickly as possible. Sometimes, however, that's easier said than done as it requires them to drift wide and engage the opposition's wide wingers. Similarly, with the asymmetrical shape and one of the full-backs dropping into the backline as the full-back/centre-back hybrid, it required the winger to drop into that vacated space for cover. However, if that wasn't quick enough, the opposition would get an opening to exploit that area and attack.

It was the same with the centre-backs jumping out to compact the first two lines, which was often targeted in transition. Bayern were good at timing those actions well so their centre-backs would often win the first or second balls and immediately instigate the next attack. However, going directly over them into the open space behind the high line or winning the ball between the defence and midfield were some of the tactics teams used to deploy against Bayern.

Final remarks

Julian Nagelsmann is one of the, if not the very best, young coaches on the planet. He's a rare positional and relationist hybrid profile who bases his systems on the players he has and tweaks them to maximise their raw talent. On the training ground, he's intense but modern, using technology, data and different tools to give his squad and staff the best possible platform to improve.

Considering Barcelona are looking for a coach with enough experience, Nagelsmann once again fits the ball almost perfectly. His progress up the ladder of elite football has been gradual, starting slowly and culminating with top clubs and a national team stint. In other words, Nagelsmann has already seen it and done it all. Throughout that period, he's also had to develop youth, manage egos, meet crazy expectations and steer his ship through turbulent seas and under questionable hierarchy. In other words, he's used to working in all sorts of different conditions.

Clubs under Nagelsmann play attacking football and dominate their opposition, a philosophy that mirrors Barcelona's view of the beautiful game. But he is not without faults. The constant tweaking has been an issue for the young coach since the early days of his career and sometimes, it can lead to players not having the clarity of role they need or the time to fully adapt.

We change our system too often during games. We're not ready for it. We're not robots, but humans, I love Julian, but sometimes we need three minutes after changing the system, because not every player understands it or can't hear it because of the 50.000 spectators. - Andrej Kramaric

It has to be said, however, that Nagelsmann is a much more practical coach nowadays; he understands elite football often needs to be simpler to be more effective. But this remains an issue because constant optimisation can be taxing on the players.

Similarly, for a coach who bases his whole philosophy on the players, he's been known to have issues with man-management, specifically with providing the human touch when necessary. Again, this may have changed of late and he is aware of how important this aspect is in coaching. Still, if he's to manage a juggernaut of a team with history, cultural riches and aspirations for greatness once again, this needs to be a clear strength of his.

Finally, even though he's used to working with all sorts of different player profiles, the current Barcelona squad is lacking in several areas and Nagelsmann, for all his pedigree and insight, might not be the best coach to ask for and pick the right players, especially at a club that doesn't have the means nor a stable hierarchy to provide him with the suitable profiles. Again, Nagelsmann has been improving in that regard as well but at Barcelona, the recruitment and profiling would need to be perfect as he would have to work with little and turn it into a lot.

But even with that being said, there's a feeling that if you truly can get Nagelsmann at your club, you should do whatever you can to do so. Is he the top choice, though? Stay tuned as we continue our search for the ideal candidate.