Xavi's bittersweet reign: Why can't Barcelona control games?

There is no denying Xavi has improved this team but it’s also apparent he hasn’t improved them enough to be a powerhouse just yet

Barcelona have been on a path to rediscover their identity for several years now. Coaches like Ernesto Valverde, Quique Setien and Ronald Koeman all had different ideas of what that actually meant but none could bring it to life. At least not the way it was meant to be brought to life.

But Barcelona’s game model may not be entirely unique. After all, it is the result of years of tweaks, input from different managers and a plethora of different player profiles, all of which are now sprinkled across the footballing world. But what their game model is, is consistent. And also apparent. It’s apparent in the way they train. It’s apparent in the way they recruit. And it’s apparent in the way they play. Or at least it should be. Lately, however, that has not been the case.

For all of Xavi’s efforts so far, Barcelona are yet to consistently attain that which has alluded them for years: control.

How do you control games?

Control is a very broad term. In football, control comes in many shapes and forms - from controlling the game by controlling the ball to controlling the game by controlling the space; Whether you’re on the offensive or the defensive, you can still have control. In the golden Pep Guardiola era, Barcelona achieved it through both of those aspects almost equally. And while under Xavi we have seen some steps in the right direction, the squad is still far away from the holy grail.

But control doesn’t have to be mindless recycling of possession either. A team can have a lot of the ball, or at least the majority of it, and still lack control of the game. For instance, Barcelona had more possession than Elche in their 4-0 stomp and yet, the second half felt anything but controlled or dominant. Why? Because the possession was not meaningful nor was it stable at any given moment. In attack, they rushed and in defence, they panicked. They still saw more of the ball than Elche, yes, but what they did with it did not encapsulate control.

Another key aspect in establishing control over the game is sustaining pressure in possession well. This equates to pinning the opposition down and not letting them escape or breathe. In that sense, sustaining pressure usually increases the tempo and leads to several fast attacks one after the other so it isn’t necessarily about one long phase of possession but rather about constantly retaining it to immediately commence the next offensive. That, too, is a form of control. You’re controlling the game by limiting the zones in which the opposition can play. Barcelona used to be very good at it but lately, they’ve swapped the sustained pressure approach with a highly transitional one. Was this done purposefully? That’s what we’ll try and find out.

To successfully sustain pressure, you need to be able to pin the opposition back and not let them out. And you do it through technical quality, athleticism, counter-pressing, duelling and above all, through an excellent structure in and out of possession, which includes both positioning and movement. So much of what happens in the final third is the result of things that came before it. You can’t have a successful siege high up the pitch if your first and second phases are unstable. It’s all connected.

That’s also where issues for Barcelona arise. They don’t sustain pressure well because they don’t have stable possession phases before attempting to sustain pressure. They lack control of the game because they can’t control the zones where the opposition is active and impactful. There are several reasons why that is so and we’ll explore them next.

Verticality triggers

Verticality has been a well-known and well-documented issue for Barcelona. I talked about it months ago and the fact it’s still prevalent is a problem in itself because it can signal a lack of intent or even inability to solve it. But verticality can also be a game model. In fact, for some, it’s a viable one. But not for Barcelona. Why? Not because of some age-old motto or belief that Barcelona shouldn’t play that way, although that is also relevant in this discussion. It’s largely because Barcelona don’t have the players nor the fitness level to sustain that game model.

Think of the peak Liverpool squad under Jurgen Klopp that used to overrun the opposition through their verticality. They thrived in that game model because they had the players for it. The current Barcelona setup often plays a similar style but without the necessary elite transition profiles for it. It could also be why their key players are often injured - they’re exhausted playing a style that doesn’t suit them.

Recently, I spoke about Barcelona’s verticality triggers. In essence, there are certain areas of the pitch that prompt their players to go long and go direct. Those are most notable in the full-back/wide centre-back zones.

This isn’t that big of a surprise given Xavi’s insistence on the overload-to-isolate tactic. The 146 long balls from the LB zone are mostly diagonal switches to the isolated RW, as are many of the central corridor’s attempts too. The RB area is the same with diagonals into space for the likes of Balde. These are Barcelona’s clear avenues to attack and exploit space. But what are the issues with this setup? Profiles.

On the left, Barcelona don’t have a winger who’ll effectively attack space. Ansu Fati is better used in a minimum-width role, close to the box and with a narrower position. Ferran Torres isn’t nearly as good in 1v1s or in a highly creative role on the left as his pace, final delivery and dribbling are all lacking in that area of the pitch, too. The full-backs are somewhat better, though. Alejandro Balde is athletic and fast so he can blitz markers and conquer the space behind. If it exists. If it doesn’t however, I find his 1v1 underwhelming and predictable as he heavily favours his left foot in such engagements. But assuming he does run past the marker, his final ball and timing of runs still need refinement to be effective. I’m not saying he can’t or won’t get there, the signs have been promising, but he’s not there yet.

Subscribed

Interestingly, however, Jordi Alba is a fantastic profile for that as both his timing and delivery are elite. In a setup where the width comes from the left, he is the ideal choice. Not to mention it pairs well with someone like Raphinha on the right who cuts inside on his left foot and aims for diagonals or inswinging crosses. But Alba is being phased out and could soon exit the club and that will create a big hole on the left once more.

On the right, without Ousmane Dembele, the situation is similarly bad. Kounde or Ronald Araujo can’t hold width or attack space while Raphinha is a minimum-width type of player too. He can’t offer reliable 1v1 proficiency in large spaces and doesn’t necessarily want to constantly attack space in behind either.

.@Jon_Mackenzie's video on minimum width is relevant here.

— Domagoj Kostanjšak (@DKostanjsak) April 8, 2023

In the overload to isolate tactic, Xavi relies on maximum width to isolate the RW, in this case Raphinha.

But he's a minimum width player who curves inward.

He needs to be closer to goal.https://t.co/vgVYnDtp2i

The sheer number of those long passes being deployed isn’t that big of an issue, though. Compared to the likes of Arsenal, Manchester City or Napoli, for instance, they have the second-most long balls from those areas out of the four teams but not significantly more. On the other hand, they do have more long possessions (between 10 and 30 seconds) in the middle third than any of the other teams mentioned. But it’s the tendency to insanely speed up the game once the ball reaches those zones that is an issue.

Essentially, wide centre-backs or full-backs attaining possession there instantly triggers runners: Barcelona immediately expand the pitch, not shrink it, inviting long deliveries into space rather than short link-up opportunities, even if they are available or can be manufactured.

Here are two such examples. In the first one, upon receiving possession from the goalkeeper on the right, Barcelona immediately penetrate the half-space to attack vertically. Having Gavi, in particular, in such a role isn’t necessarily optimal either. He won’t beat the defender for pace (which is how they lose possession in that sequence) nor will he reliably dribble past him. Instead, slowing down once the play has progressed past the first line of press is more desirable.

A similar thing happens in the second image where the possession is with the wide centre-back on the right. At that moment, the interior (intriguingly Gavi again) immediately wants the ball into space, distancing himself from his midfield partners and inviting a long pass. This nullifies Barcelona’s retention efficiency and kills any chance of recycling to reach the free man on the other side, an option that could be manufactured through different (and better) movement and space occupation. This, as we’ll see again further down the line of this piece, is a key issue: Barcelona’s midfielders are tools to pin the backline and offer outlets but is that their optimal use? I would argue not.

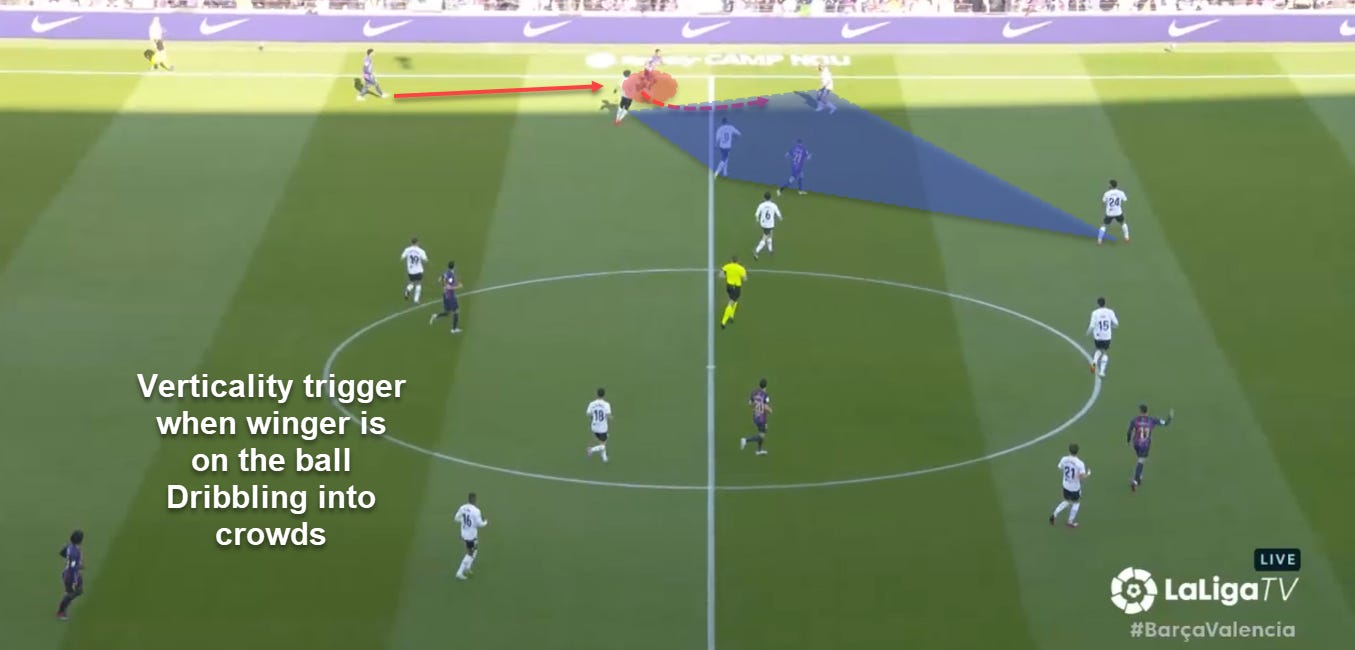

Another heavy trigger is the behaviour of Barcelona’s wingers and full-backs in those areas. They rarely slow down the game. Instead, upon receiving possession, their first instinct is to attack.

Look at Fati’s decision in the image above. He receives the ball in a very crowded area and yet, the first thing he does is dribble straight into it. Needless to say, Barcelona waste their chance to retain, recycle and control and instead lose possession in that sequence. This isn’t a critique solely of Fati. He is guilty of this but the worse problem is he’s not a lone culprit. Raphinha does a similar thing and so do Balde and Ferran. Could this then be an instruction rather than instinct?

This dribbling into crowds issue is even more emphasised when paired up with suboptimal space occupation. In fact, I could even argue it’s a direct result of it. After all, if you don’t have other options, you will inevitably try and be proactive, even if it means the odds are against you and you’re alone in the attempt to do so.

The sequence below is a good example of this.

Ferran makes the mistake of dribbling into a minimum of three players ahead of him but the lack of half-space support makes any other play similarly difficult to execute. Gavi is too deep and central runners are tough to access. The other option is to go back or stop and re-organise the attack. Again, that does sound like a better option but Barcelona rarely take it.

Even if the structure is good for retention, that slower and more methodical route will rarely be taken. In that sense, it’s not so much about the number of long balls but the situations in which they are used. Are they the only way out of a press? Are they the only chance-creation tool in that given moment? Or are they the game model itself?

Here are two other examples of verticality triggers with a potential for going down a different, more stable route.

We can discuss the possibility of Barcelona being forced into long passes but if the team regularly defaults to that option despite having other routes accessible to them, what does that signal then? Is verticality a preference, a game model?

Either way, all of that talk of structure, positioning and decision-making is a great segue into the next issue(s) we have to discuss.

Game state & space occupation

I’ve already alluded to the connection between structure and verticality earlier in this analysis. Sometimes, the lack of the former forces the latter as the answer. In Barcelona’s case, this has been prevalent and continues to be so, albeit in spurts. What I mean by this is that Barça can be both an extremely functional and well-structured team and a blatantly disorganised and panicky one, often within the same 90 minutes of a single game.

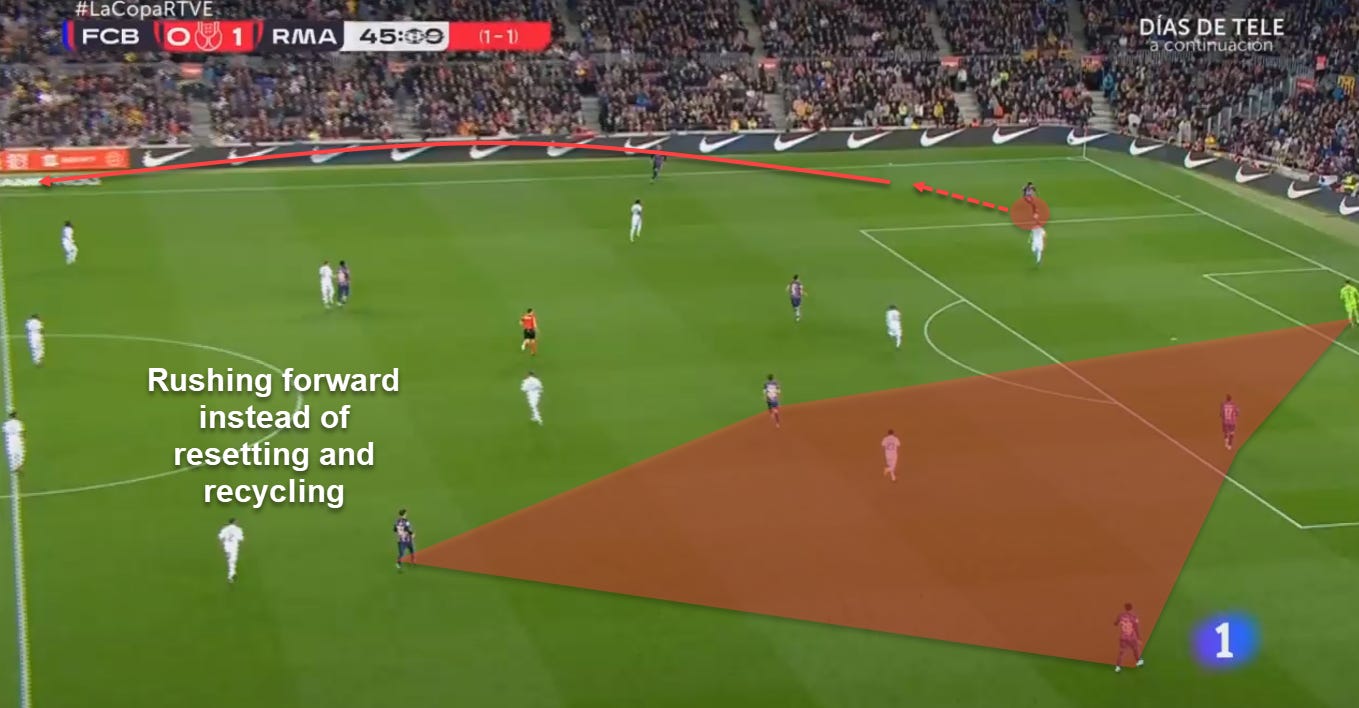

This was most evident in their Camp Nou debacle in Copa del Rey against Real Madrid. In the first 45 minutes, they were a collective guided by a clear game model; a team who dominated Real Madrid for almost the entirety of the first half. In the second 45 minutes, they were an impatient, disorganised and overly vertical shadow of their true self. One team dominated, the other got dominated. And the worst thing is, they are one and the same side; entirely identical but painfully different at once.

Inevitably, this is also where we have to talk about mentality. Barcelona are notorious for crumbling when the going gets tough and often start spiralling at the first sign of trouble. In the Clasico, it was the 46th-minute goal that shattered their dominance into little blaugrana pieces. All of the issues that usually arise were well and truly present against Real Madrid. Not only that but they were also dialled up to 11. But I’ve also checked the numbers to see if there’s any objective reason to believe this is a recurring theme.

There’s no significant difference between Barcelona’s first and second-half performances. Yes, they generally have less possession, fewer passes (long and otherwise) and fewer shots but they somehow register more xG too. What does affect them more significantly, however, is the game state. When they are losing, Barcelona will generally tally significantly fewer passes with less accuracy (320.63 vs 250.64 on average with 89% accuracy vs 86.8%), less xG (1.12 vs 0.78), fewer shots (7.12 vs 6.27) and they’ll play at a slightly slower tempo with slightly longer average passes and slightly fewer passes per possession.

In defence, they register slightly lower PPDA when losing, which would indicate an increase in pressing intensity, but register and win fewer defensive duels, concede more goals and intriguingly, face fewer shots but with a drastically better conversion rate for the opposition. I mention all of that because game state heavily impacts Barcelona’s ability to control games. And it’s directly tied to their structure and space occupation. Against Real Madrid, game state and psychological burden were prerequisites to the collapse of the structure. But that wasn’t the only fault - the triggers we talked about earlier were emphasised and made the situation far worse even when there were other options to explore.

Against Real Madrid, we saw Barcelona abandon their principles and game model and as soon as they were ready to compromise and change, the match suited their opposition far more. But the examples don’t stop with the Clasico. Yes, Barcelona will often choose the vertical route even with other options possible but often, they will also have no other choice.

Suboptimal space occupation always invites verticality. If you don’t have close proximity players to link up with, chances are you’ll be forced into a far more direct route. That is often the case with Barcelona regardless of the game state. When we look back at the 4-0 thrashing of Elche, that problem is particularly prevalent and is also why Barcelona failed to dominate despite the dominant result.

These instances you can see below are not the result of poor individual quality. Better players would improve the system but things like movement and space occupation or a better structure don’t depend on better individuals. These are coachable aspects that have to be ingrained in the game model. They have to be present across the squad, both the starting XI and the bench.

A quick note for the first image: the player in the right half-space is an Elche player but the yellow colour of the edit makes it seem like he’s a Barcelona player in a yellow shirt. He is not. Barcelona are once again using maximum width with no supporting options, which forces them to go long. In both images, there’s no half-space presence to open a channel for the ball-carrier so they go long. The unit is not compact across the pitch and they have players occupying the same vertical (and horizontal) channels at the same time, making them easier to mark out of the game. Staggering properly is key in space occupation.

Come to think of it, that Elche game is a demonstration of poor decision-making, dribbling into crowds, poor space occupation and verticality triggers all at once. It’s why I was highly critical of Xavi even after such a (seemingly) dominant victory. I already used a couple of examples from that game in the previous section of the analysis and a couple here again but there’s more.

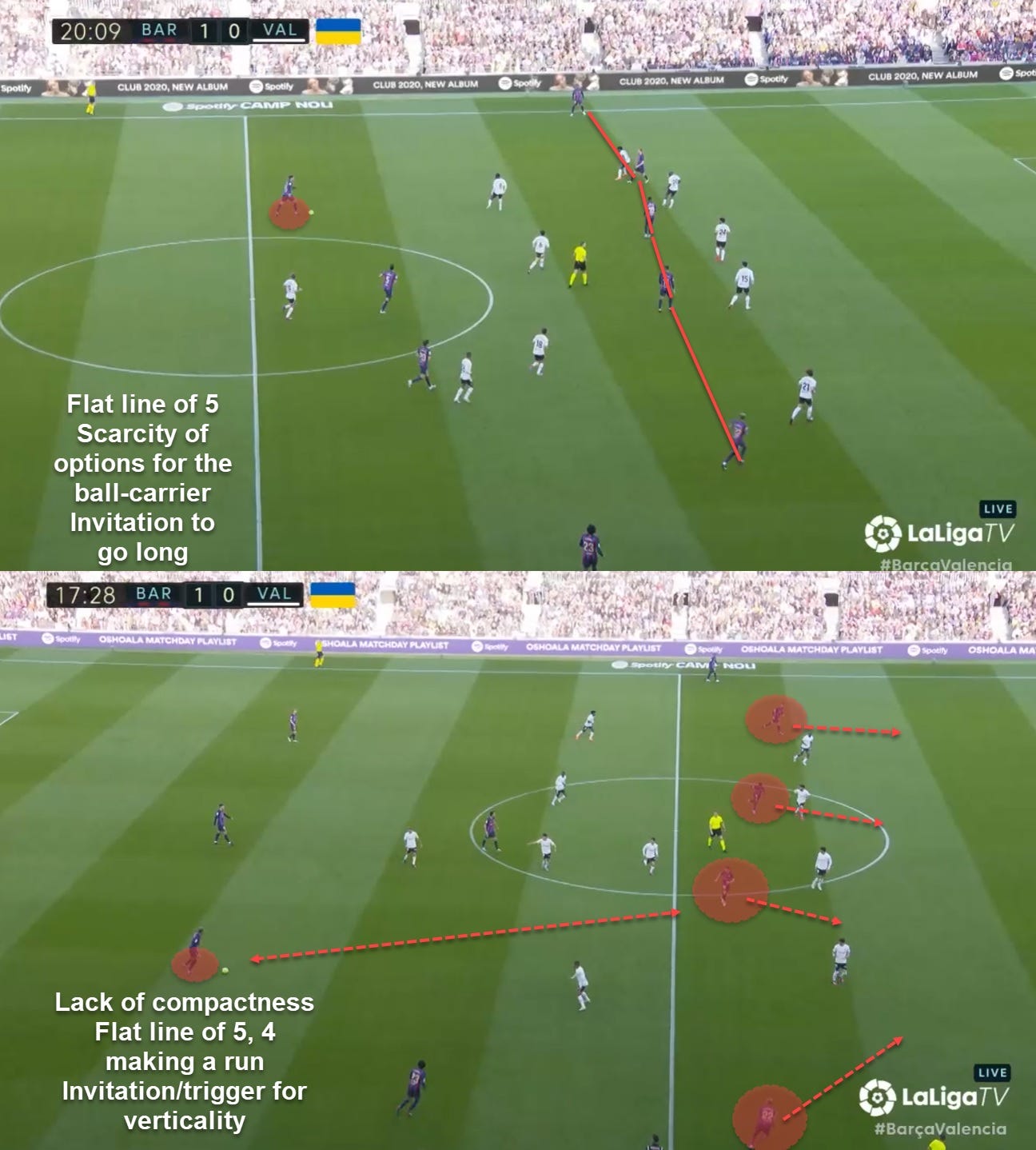

Most of these situations are also connected to compactness. When you’re not compact, retention becomes that much more difficult to achieve. That too invites verticality. And Barcelona are still at fault for this quite too often. Yes, there are indeed instances when their unity and compactness can and should be praised, but the fact it’s still far too inconsistent despite being highlighted as a major flaw months ago is concerning.

When this lack of compactness is most prominent is when Barcelona push their players up to create an attacking line of five. In such a scenario, the interiors are often occupying the half-spaces and the only viable pass is a long and direct one.

Barcelona’s space occupation in the first image opens the channel to access the wide man directly but where do they go from there? The line of five lacks staggering and the positioning of the ball-carrier is once again the verticality trigger, prompting runs away from the ball, not towards it.

A similar thing happens in the second sequence. Barcelona have avenues to explore other than a lofted pass beyond the opposition’s backline but choose not to willingly. Araujo, in particular, is guilty of this. When the Uruguayan finds himself in this position with the ball, he will go long far too often. Just because you can make the pass, doesn’t mean you should. But notice how many runners Barcelona have at that particular moment.

No one is even attempting to link up, they are all triggered to make the run. So Barcelona don’t even attempt a slower build-up, even though they can and probably should.

And needless to say, this too affects their ability to control games.

Final remarks

No team is without faults. But the worst thing about Barcelona is that their faults are old and well-documented. I’ve already written a similar article on these issues months ago and while there has been improvement, the alarming thing remains their presence in the present day.

There is no denying Xavi has improved this team but it’s also apparent he hasn’t improved them enough to be a powerhouse just yet. Of course, nothing is purely black and white and the same goes for his stint at the Camp Nou. We can praise him when he earns the praise but we can also criticise when criticism is needed.

All of this doesn’t mean the project has been a failure. But it does mean we’re still far from where we need or want to be: the squad is incomplete, the structure still has holes and the game model isn’t fully ingrained into the team as of yet. But it’s also possible this is at least a variation of the game model the new coach wants to practice. For all the comparisons with Guardiola, Xavi may be closer to Johan Cruyff in the way his team approaches verticality. ‘With this style, we have won five Champions Leagues. Johan Cruyff created it. It has borne fruit and results,’ he said after the painful defeat to Eintracht Frankfurt. But the Cruyff style isn’t necessarily identical to Pep’s. Far from it, even.

Either way, I keep saying it because it is still true - Xavi has work to do. It doesn’t mean I don’t believe in or don’t hope for his success. Quite the opposite, in fact. But it’s important to note both the good and the bad equally. And that’s what I’m doing.

Força Barça